Flows & Liquidity

Financial conditions impulse remains positive

- Our proxy for the financial conditions impulse remains positive, posing some upside risks for growth and inflation.

- The PBoC has been more contrarian than other central banks in terms of gold purchases.

- SEC’ Wells notice to Robinhood should not pose an obstacle to an eventual spot ethereum ETF approval.

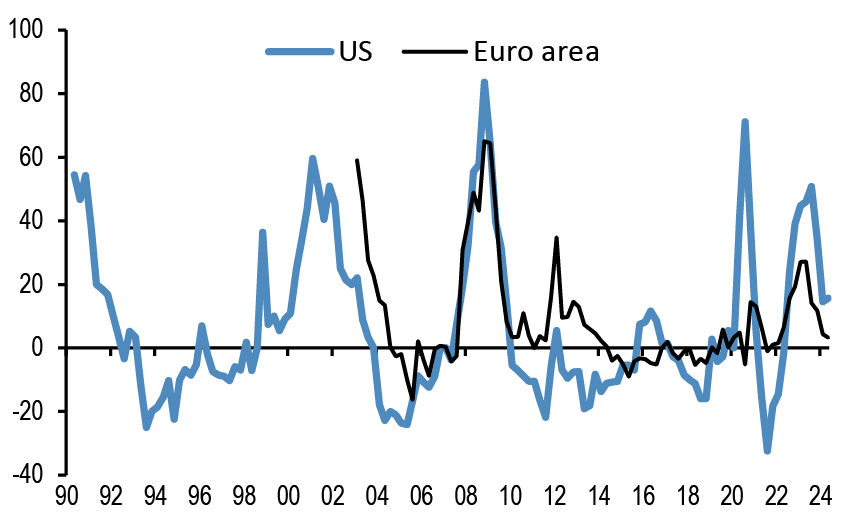

- After the release this week of the Fed’s senior loan officer survey, along with the ECB’s bank lending survey that was released a few weeks ago, financial conditions have again featured in our conversations. After the significant decline in respondents reporting a tightening in lending standards in both the US and the Euro area in the 1Q24 surveys, the latest survey suggested a modest tightening for the US in 2Q and a continued modest decline to close to zero for the euro area.

Figure 1: Net percentage of banks reporting tightening standards for US C&I loans to large and middle-market firms and Euro area loans to all enterprises

In %.

Source: Federal Reserve, ECB, J.P. Morgan.

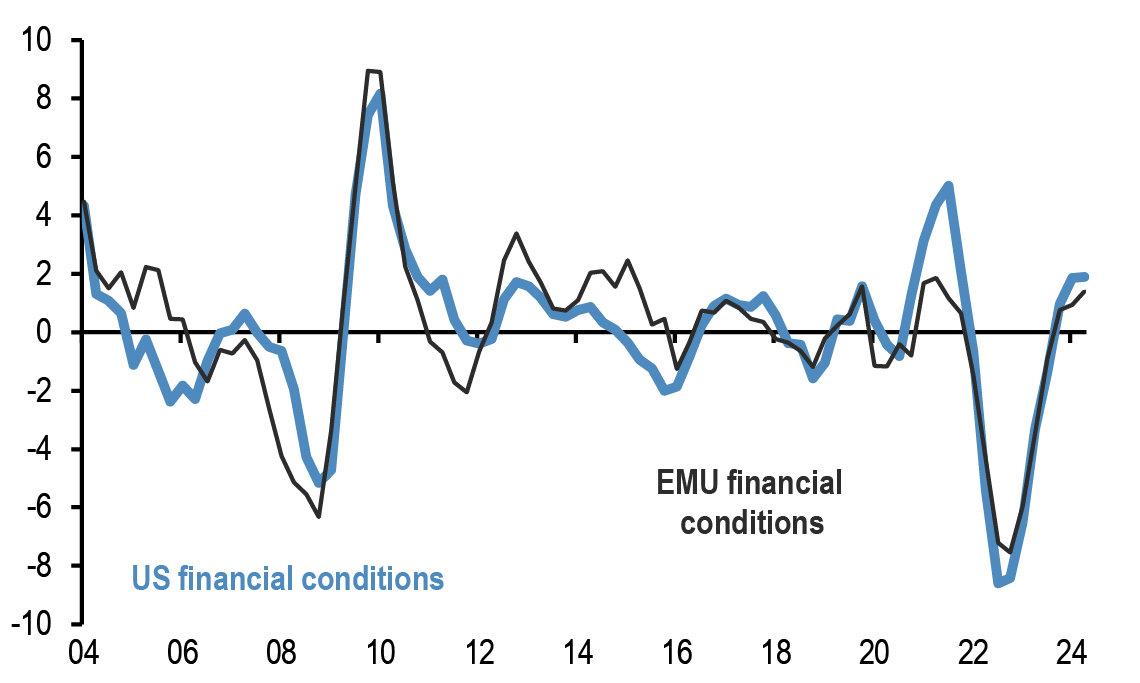

- What about financial conditions more broadly? In order to look at this, we update the financial conditions framework (see e.g. F&L, Sep 2016) built on a paper by Kasman and Mackie, Aug 2008, on quantifying the impact of financial market developments and monetary policy actions on economic activity. They drew on a methodology described in the IMF paper “A US financial conditions index: putting credit where credit is due” by A. Swiston, who estimated the impact of changes in six financial variables on the level of GDP after one to two years. The six financial variables are: 12-month changes in the 3-month short rate, the yield on investment grade corporate bonds, and the spread of high yield corporates over that of high grade, as well as 12-month real equity returns and the 12-month change in the real FX rate and bank lending standards for businesses as reported in loan officer surveys.

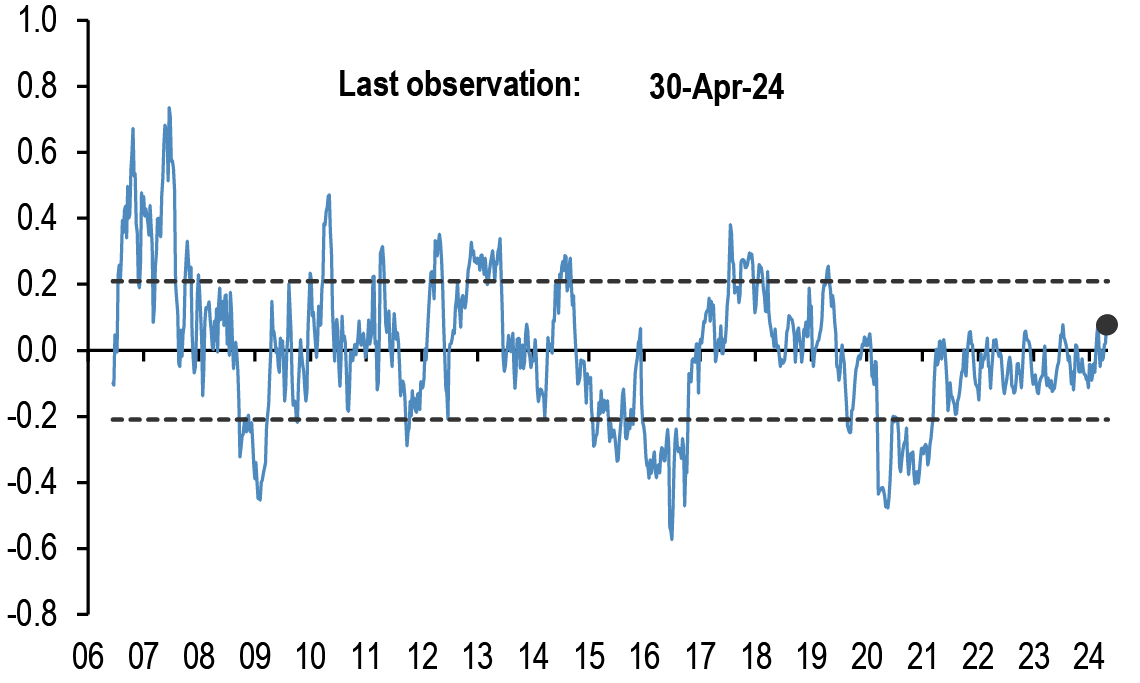

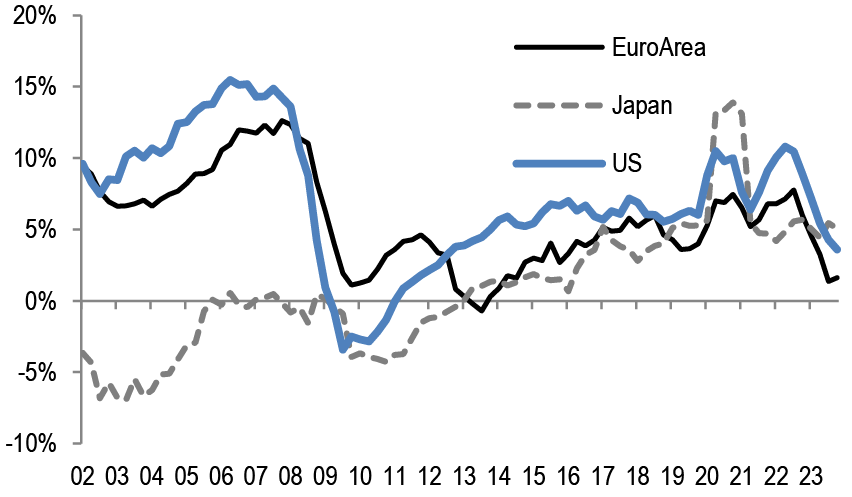

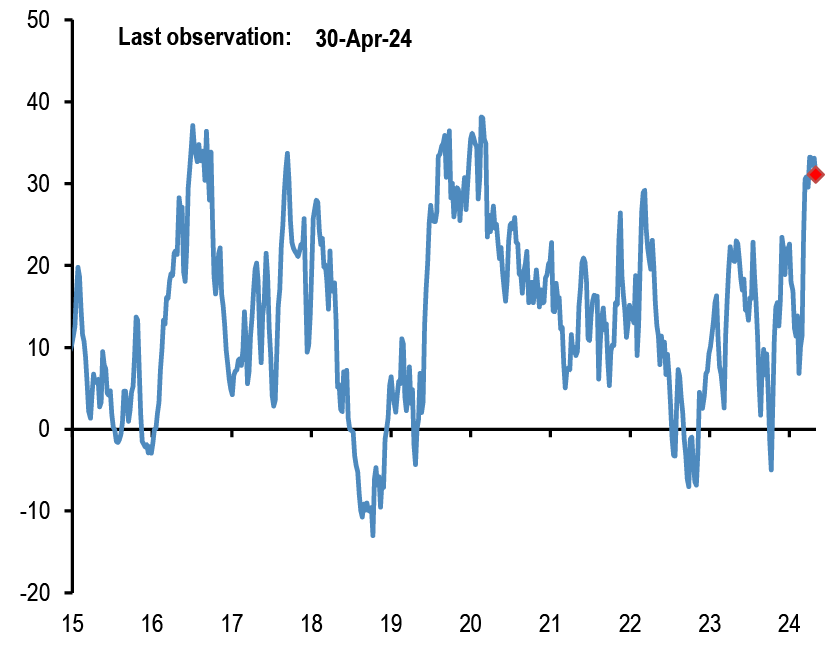

- This financial conditions indicator is depicted in Figure 2 for the US and the Euro area. It shows that financial conditions steadily improved from their peak tightening in 2H22 to a net loosening by 4Q23. Moreover, this has been a broad-based improvement as the effect of past yield rises has faded, equity returns turned from a headwind to a tailwind and lending surveys have eased back significantly from their previous peaks. Based on quarter-to-date data for 2Q24 on 12-month changes to rates, spreads, returns as well as the 2Q24 lending surveys, this positive impulse from financial conditions appears to have continued.

Figure 2: Change in financial conditions in the US and Euro area

Positive (negative) numbers represent easing (tightening) in financial conditions.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

Figure 3: US and Euro area financial conditions indicators

This table is based on IMF working paper 08/161 – “A US financial conditions index: putting credit where credit is due”, by Andrew Swiston. HY spreads are measured relative to the yield on HG debt. Bank lending standards only cover C&I lending. The level shows each financial variable as at 4Q22 and 2Q23. For yields the level is the 12-month change in basis points; for real equity returns and the real exchange rate the moves are 12-month % changes; for bank lending standards it is the %pt change in the % of banks tightening standards for C&I loans. The impact is the effect on the level of GDP of these moves in financial variables after one year.

| US | Euro area | |||||||

| 4Q22 | 2Q24 | 4Q22 | 2Q24 | |||||

| Change | Impact | Change | Impact | Change | Impact | Change | Impact | |

| 3m rate (bp) | 456 | -2.4 | 4 | 0.0 | 270 | -1.4 | 21 | -0.1 |

| HG yield (bp) | 267 | -2.2 | 15 | -0.1 | 303 | -2.9 | -25 | 0.2 |

| HY spread (bp) | 185 | -0.5 | -105 | 0.3 | 176 | -0.5 | -70 | 0.2 |

| Real eq return (%) | -23 | -0.9 | 19 | 0.7 | -24 | -0.9 | 11 | 0.4 |

| Real fx rate (%) | 4.4 | -0.3 | 1.4 | -0.1 | 20.0 | -1.3 | 3.1 | -0.2 |

| Loan officer survey | 57.3 | -2.1 | -30.4 | 1.1 | 18.4 | -0.7 | -23.9 | 0.9 |

| Total | -8.4 | 1.9 | -7.5 | 1.4 | ||||

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

- As we have noted previously, the methodology in the IMF paper estimated that the impact from a tightening in financial conditions on GDP typically takes between one and two years to be fully felt. While this suggests that the effect of previous tightening should be fading over time, and will increasingly be offset by the loosening that has taken place in 4Q23 and the first half of 2024. While in 2H23 central banks had pointed to tighter financial conditions substituting for further rate hikes, they appear to have largely de-prioritised financial conditions as they shifted to a tailwind. But this shift may have contributed to the positive inflation surprises since the turn of the year in the US. And to the extent they have, the catch-up in euro area financial conditions could mean that while the ECB is determined to start an easing cycle in June it could be challenged over further cuts in 2H24.

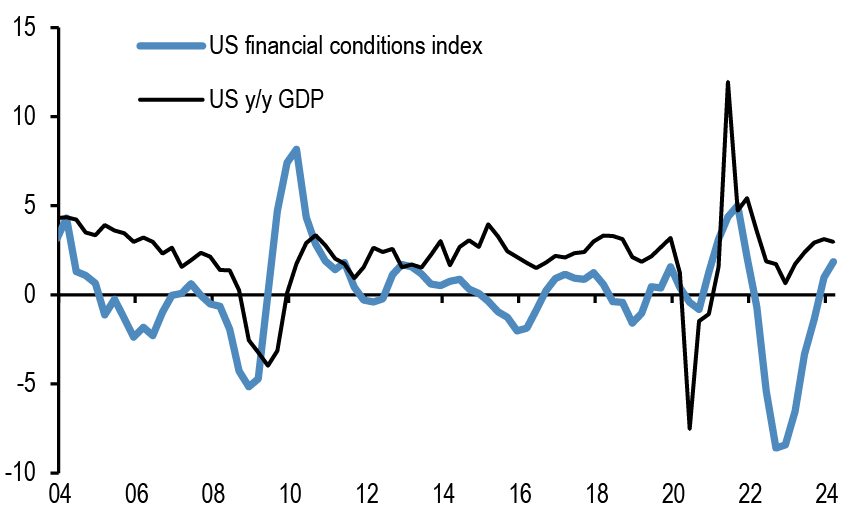

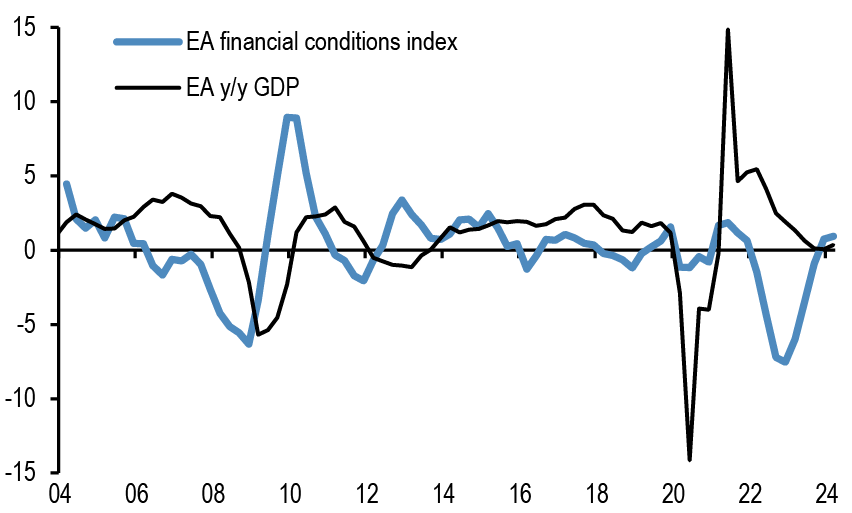

- To look at the relationship between financial conditions and growth, Figure 4 shows the financial conditions indicator for the US along with y/y real GDP growth and Figure 5 shows the same for the Euro area. Looking at the relationship around the time of the financial crisis, the trough in the financial conditions index (i.e. peak tightening) preceded the trough in y/y real GDP growth by around 2 quarters, while in 2022 the financial conditions trough in 3Q22 was followed by a trough in y/y real GDP growth by one quarter. For the euro area, the 2008 trough in financial conditions occurred one quarter before the trough in real GDP growth, while the trough (peak tightening) in end-2011 preceded a trough in real GDP growth by more than a year. In the current conjuncture, the trough in financial conditions in 4Q22 was followed by a trough in real GDP growth after four quarters.

Figure 4: Financial conditions index and y/y real GDP growth for the US

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P Morgan.

Figure 5: Financial conditions index and y/y real GDP growth for the Euro area

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P Morgan.

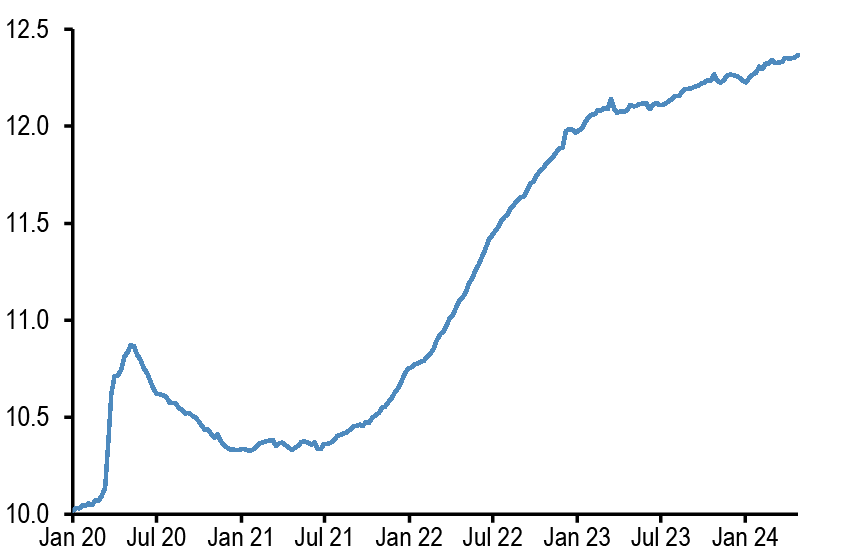

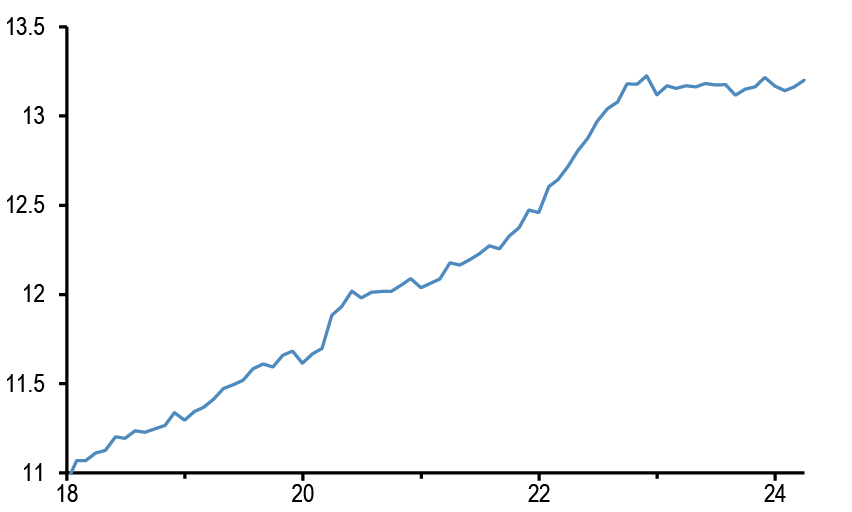

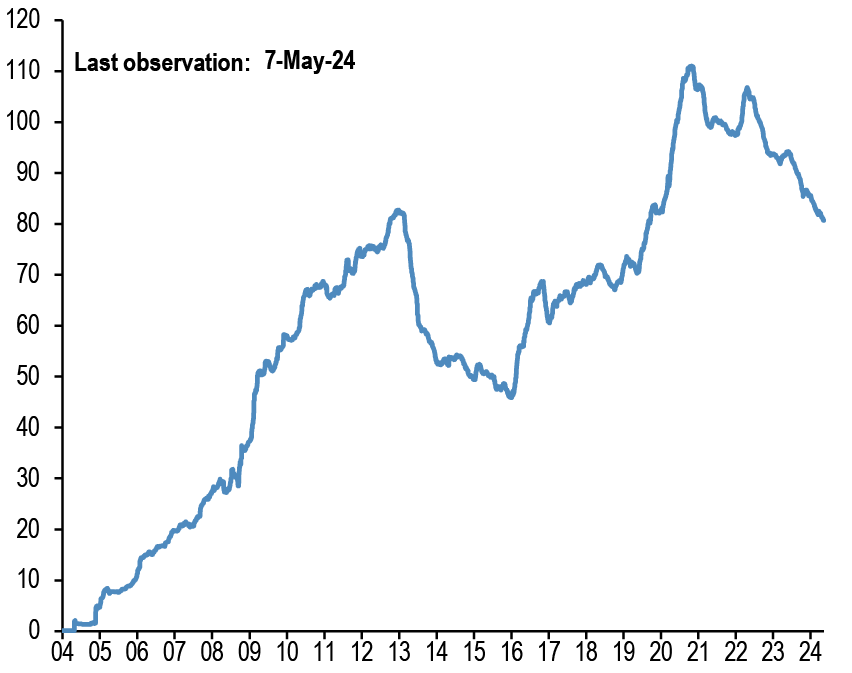

- What about the quantity side? To look at how credit creation has evolved, we turn first to bank lending activity. Figure 6 shows outstanding loans and leases on bank balance sheets from the Fed’s H.8 release, and suggests that, after pausing for around a quarter in the aftermath of the SVB crisis, loan growth resumed from mid-July, paused again around year end before picking up from the first week of January. Since then, loan growth has averaged an annualized pace of around $460bn. As we have argued previously, this growth is at least in part due to the liquidity offset from the declining use of the Fed’s ON RRP facility that more than offset the rebuild of the TGA and the balance sheet contraction largely due to QT and helped avert a more protracted contraction in bank liquidity that would have weighed on lending growth. However, with much of the ON RRP facility having been unwound, loan growth at the YTD annualized pace is likely required just to offset the effect of ongoing QT. Indeed, in the euro area where QT and maturing TLTRO’s have seen a contraction in reserves in the absence of an offset, loan growth been largely flat since November 2022 ( Figure 7). The level of outstanding loans in the euro area remains below its November 2022 level, though data for the first three months of the year suggests some signs of recovery with annualized loan growth of close to €135bn.

Figure 6: US commercial banks’ loans and leases

$tr.

Source: Federal Reserve, J.P Morgan.

Figure 7: Euro area bank lending to non-banks excluding general government

€tr.

Source: ECB, J.P. Morgan.

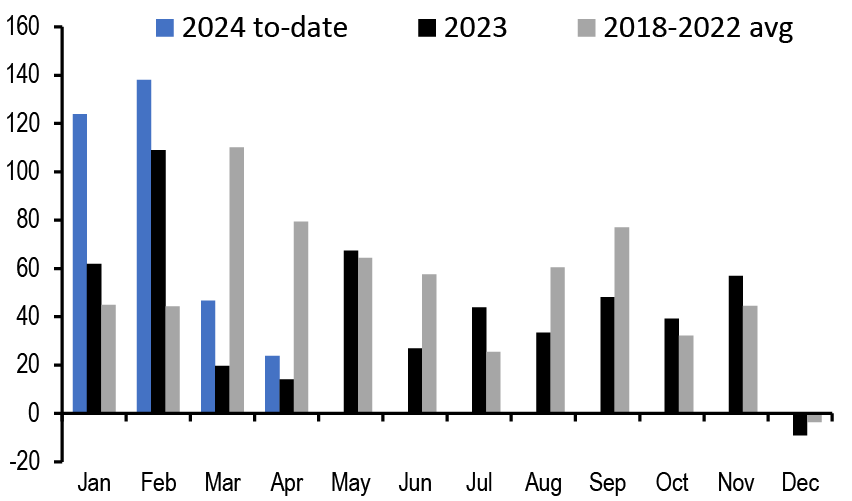

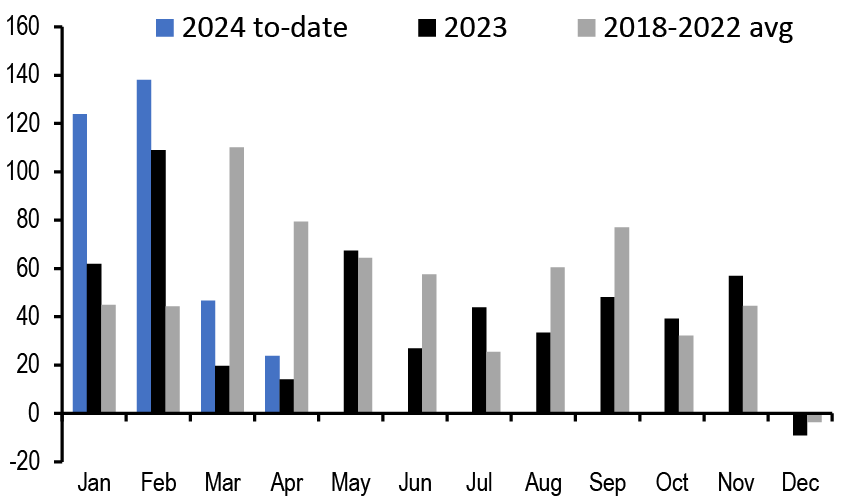

- Another source of credit creation is through net issuance of debt securities. Figure 8 shows the monthly net issuance of US HG bonds for 2024 to-date, as well as for 2023 and the average for the previous five years. The significant strength of net issuance in January and February saw 1Q24 net issuance reach around $310bn, the second strongest quarter since 2000 after 2Q20, though there appears to have been some front-loading of issuance as the pattern for the first four months is surprisingly similar to 2023 with a drop-off in the pace in March and April. Similarly, net issuance in Euro HG bonds has been similarly strong at around €109bn YTD, compared to 2023 issuance of €128bn (European Credit Weekly, May 3rd), suggesting that while loan growth has remained muted credit growth via capital market issuance has been strong.

Figure 8: Monthly net issuance of US HG bonds

$bn.

Source: Dealogic, J.P. Morgan.

- In all, the above suggests the financial conditions impulse remains positive, posing some upside risks for growth and inflation.

The PBoC has been more contrarian than other central banks in terms of gold purchases

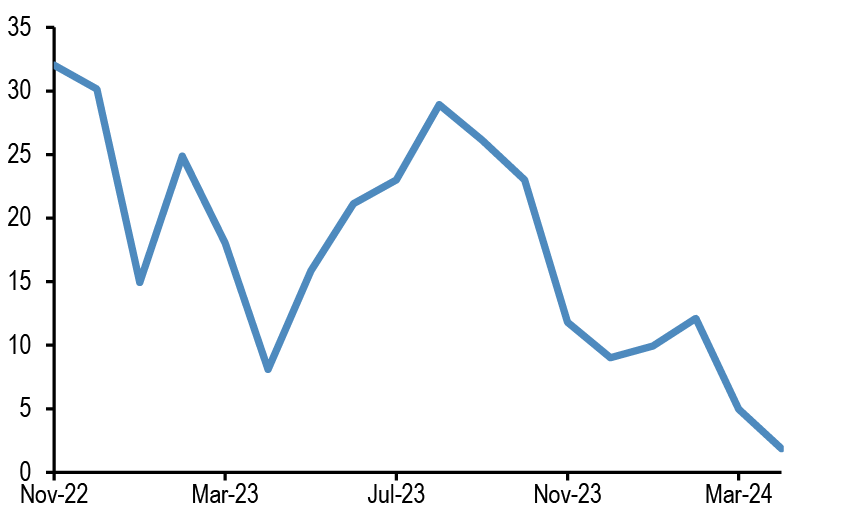

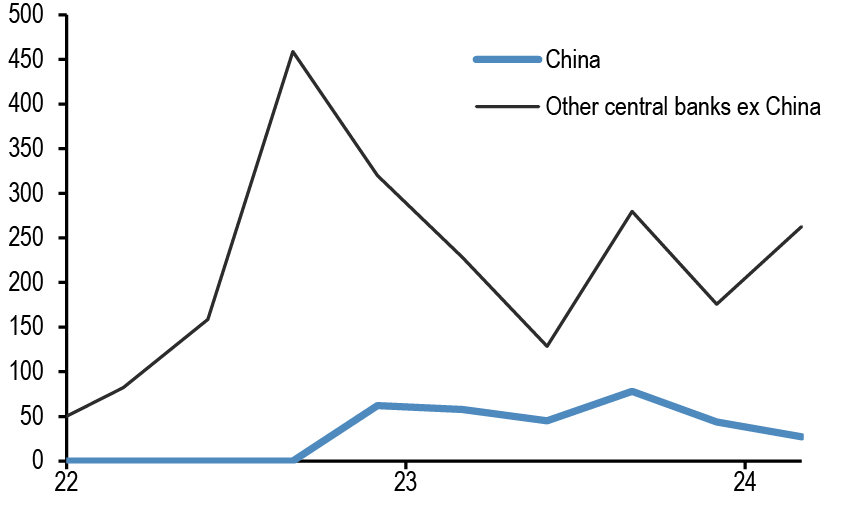

- This week’s release on China’s FX reserves revealed further slowing in gold purchases by the PBoC in April. Figure 9 shows that April saw the lowest monthly gold purchases since the PBoC started buying gold in November 2022. April reflects the second month in row the PBoC slowed its gold purchases considerably, perhaps in response to rising gold prices, thus pointing to contrarian behavior.

Figure 9: Monthly gold purchases by the PBoC

Tonnes.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

- In fact, by looking at quarterly flows in Figure 10, it looks like the PBoC has been more contrarian than other central banks in terms of gold purchases. While the PBoC slowed its gold purchases considerably in Q1, other central banks stepped up. And further back, looking at the correlation between quarterly gold purchases and quarterly gold price changes since Q4 2022, this correlation stood at -42% for China vs -34% for other central banks ex China.

Figure 10: Quarterly gold purchases by the PBoC vs other central banks

Tonnes.

Source: World Gold Council, Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

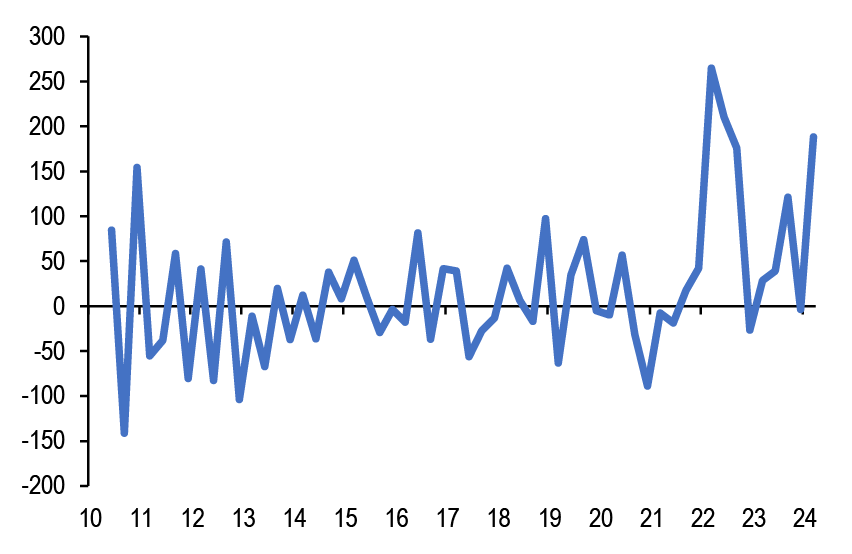

- The high overall gold purchases by central banks in Q1 have once again perturbed the historical sensitivity of gold prices to real bond yields. This is shown by the abnormally high residuals in Figure 11. These residuals are based on a linear regression of quarterly changes in the XAUEUR price to quarterly changes in the 10y real UST yield. We use the gold price in euro terms (i.e. XAUEUR) rather than dollar terms to adjust for changes in the price of dollar. As with other commodities, dollar is the settlement currency for gold and thus the gold price tends to be inversely related to dollar changes. One can see that the quarterly gold price change had been a lot higher in Q1 2024 (by around €200) than what the rise in the 10y real UST yield would typically imply. The typical sensitivity in the regression of Figure 11 is that each 100bp rise in the 10y real UST yield results to €209 decline in the price of gold and vice versa.

Figure 11: Residual from regressing quarterly changes of the XAUEUR price to quarterly changes in the 10y real UST yield

In euros.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

- There is little doubt that the pace of central bank purchases is key to gauging the future trajectory for gold prices. Indeed, the importance of central bank gold purchases has risen since the pandemic as shown by the correlation table of Figure 12. While before the pandemic gold ETF flows was the demand component exhibiting the highest correlation with gold prices, and thus the most important flow to watch, after the pandemic it has been central bank flows showing the highest correlation with gold.

Figure 12: Correlation between changes in (adjusted) gold prices with changes in gold demand

Correlation between changes in gold prices adjusted for dollar and real yield changes (i.e. the residuals of the regression in Figure 3) to quarterly changes of various demand components.

| Correlation with regression residuals | Pre-pandemic | Post-pandemic | ||

| Jewellery fabrication | -0.24 | -0.29 | ||

| Technology | 0.04 | -0.29 | ||

| Total bar and coin | -0.07 | -0.13 | ||

| ETFs & similar products | 0.37 | -0.01 | ||

| Central banks & other inst. | -0.35 | 0.46 | ||

| OTC and other | 0.04 | -0.14 | ||

Source: World Gold Council, J.P. Morgan.

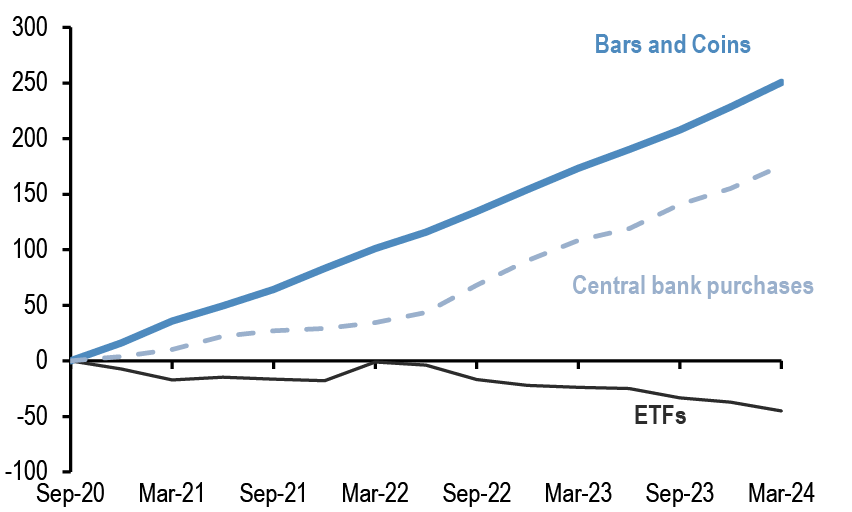

- The fading of gold ETFs as an important demand indicator likely reflects a structural shift by private investors such as individuals and family offices away from physical gold ETFs to bars and coins. Privacy and tangibility have become a more important consideration for private investors since the pandemic and physical gold ETFs have a disadvantage in this respect relative to holding bars and coins. ETF transactions are recorded and their holdings are registered, thus lacking privacy and anonymity. And in a hypothetical catastrophic scenario for which investors are trying to hedge by buying gold, holding a paper certificate of gold ownership via an ETF, subjected to counterparty risk, looks less attractive and less safe than tangible gold stored privately. Indeed, at the same time as selling gold ETFs, private investors and individuals have been buying bars and coins in a rather strong and steady manner since the pandemic. And at $250bn cumulatively since Q3 2020 these bar and coin purchases have more than outweighed gold ETF sales (-$45bn) and have even outpaced the $175bn of gold purchases by central banks over the same period as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13: Cumulative gold flows by private investors and central banks

In $bn.

Source: World Gold Council, Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

- With demand for bars and coins by both private investors and by central banks remaining on an uptrend as implied by Figure 13, it is likely that gold price changes would continue to outpace those implied by real bond yields/dollar changes (i.e. the residuals in Figure 11 would be positive most of the time) .

- For additional JPM research on gold see recent reports from our colleague Greg Shearer from our Commodities Research team.

SEC’ Wells notice to Robinhood should not pose an obstacle to an eventual spot ethereum ETF approval

- The recent Wells notice by the SEC to retail trading platform Robinhood for unregistered security offerings, took markets by surprise. This is because Robinhood is more of a traditional trading platform with a smaller crypto trading share and a rather conservative approach towards listing and delisting of crypto tokens on its platform. Robinhood doesn’t offer staking products in order to be more compliant with the regulator. And Robinhood was prompt enough to delist three major crypto tokens (Cardano, Polygon , Solana) that were alleged to be securities by the SEC in its lawsuit against crypto exchanges such as Coinbase and Binance last year.

- However, Robinhood still offers trading on another 13 crypto tokens outside bitcoin and ethereum, and the SEC appears to consider all crypto tokens outside bitcoin and ethereum as securities. This perhaps is how the Wells notice against Robinhood should be seen, as a continued attempt by the SEC to reinforce its position that all crypto tokens outside bitcoin and ethereum should be classified as securities. In our mind, via continued notices and lawsuits against crypto exchanges including those with smaller crypto business such as Robinhood, it appears that the SEC aims at influencing US policy makers and legislators, who at some point would need to pass legislation on how the crypto industry should be regulated in the US. And the Wells notice against Uniswap and Metamask (behind which is Consensys) makes it clear that decentralized platforms are not exempted from the SEC’s objective to eventually supervise most of the crypto industry.

- In our opinion, it does not look like the Wells notice should pose an obstacle to an eventual approval by the SEC of spot ethereum ETFs, although perhaps not as soon as this month . The template is likely to be similar to bitcoin: with futures based ethereum ETFs already approved, the SEC ( if it denies the approval of spot ethereum ETFs) is likely to face a legal challenge and eventually lose.

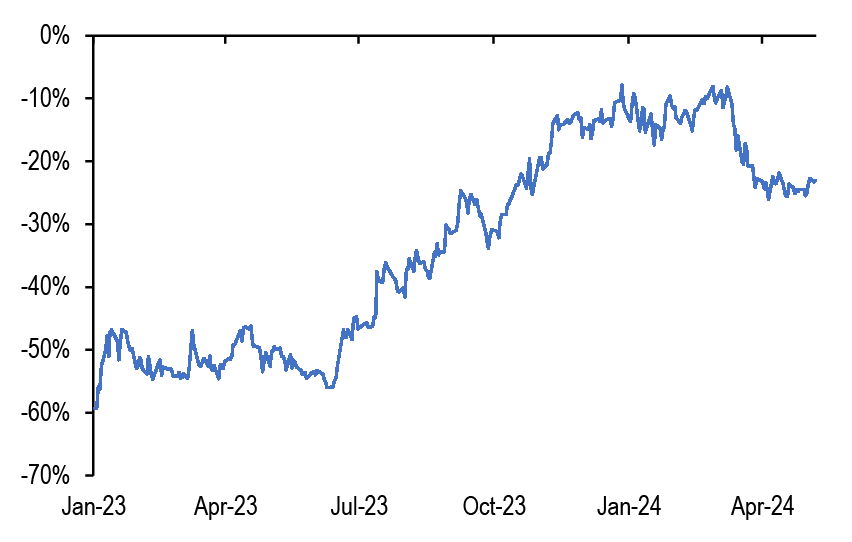

- The lack of approval of spot ethereum ETFs this month is unlikely to be a huge disappointment by markets. In general, markets do not expect an approval by this month as implied by the significant discount to NAV of the Grayscale Ethereum Trust ETHE in Figure 14.

Figure 14: Premium/Discount to NAV for the Grayscale ethereum trust ETHE

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

Appendix

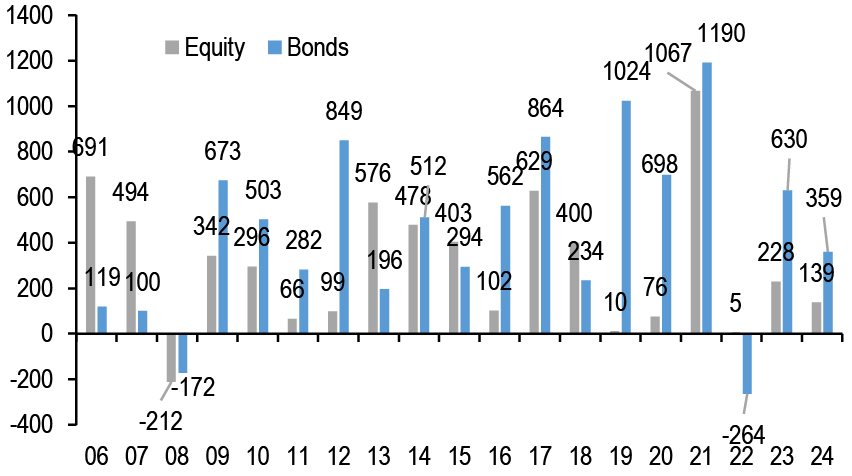

Chart A1: Global equity & bond fund flows

$bn per year of Net Sales, i.e. includes net new sales + reinvested dividends for Mutual Funds and ETFs globally, i.e. for funds domiciled both inside and outside the US. Flows come from ICI (worldwide data up to Q4’23). Data since then are a combination of monthly and weekly data from Lipper, EPFR and ETF flows from Bloomberg Finance L.P.

Source: ICI, EPFR, Lipper, Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

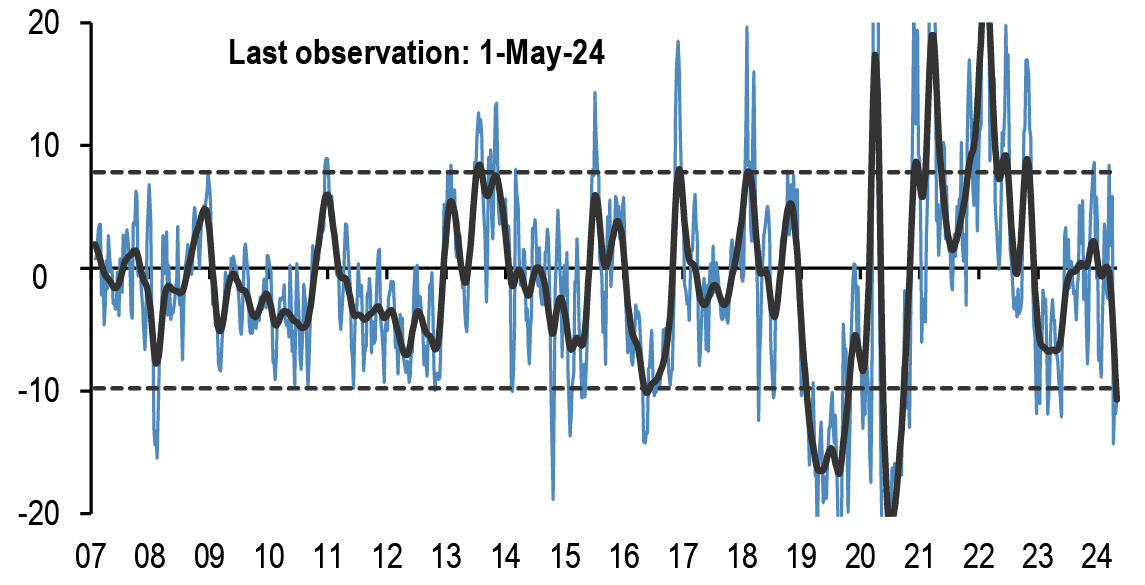

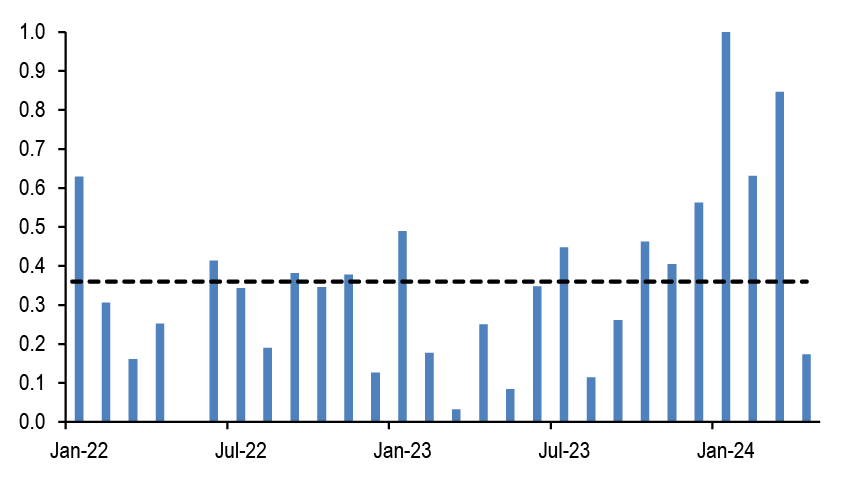

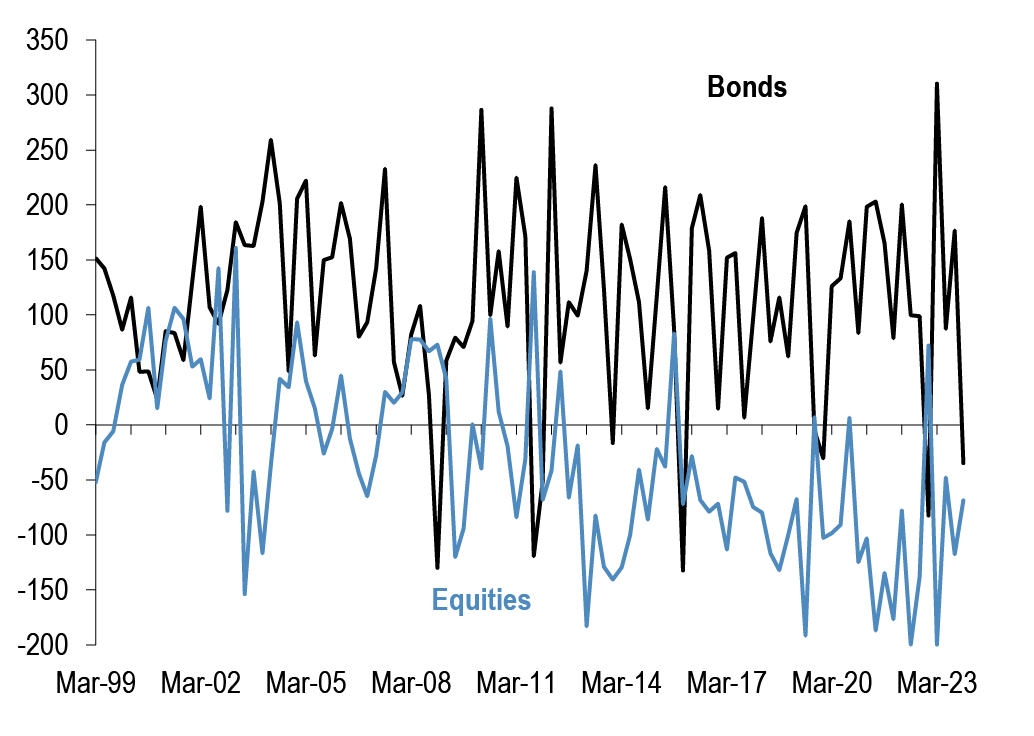

Chart A2: Fund flow indicator

Difference between flows into Equity and Bond funds: $bn per week. Difference between flows into Equity vs. Bond funds in $bn per week. Flows include Mutual Fund and ETF flows globally, i.e. funds domiciled both inside and outside the US (source: EPFR) The thin blue line shows the 4-week average of difference between Equity and Bond fund flows. Dotted lines depict ±1 StDev of the blue line. The thick black line shows a smoothed version of the same series. The smoothing is done using a Hodrick-Prescott filter with a Lambda parameter of 100.

Source: EPFR, J.P. Morgan.

Table A1: Flow Monitor

$bn per week. The first two rows include Mutual Fund and ETF flows globally, i.e.flows for funds domiciled both inside and outside the US(source: EPFR). The last fourrows only include funds domiciled in the US.International Equity funds are equity fundsdomiciled in the US that invest outside the US (source: ICI and Bloomberg FinanceL.P.).

| MF & ETF Flows | 1-May | 4 wk avg | 13 wk avg | 2024 avg |

| All Equity | 9.83 | -3.8 | 8.0 | 7.4 |

| All Bond | 4.64 | 7.0 | 10.8 | 10.5 |

| US Equity | -5.80 | -14.5 | -4.9 | -6.0 |

| US Bonds | 3.57 | 1.6 | 8.4 | 8.1 |

| Non-US Equity | 15.63 | 10.7 | 12.8 | 13.4 |

| Non-US Bonds | 1.07 | 5.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| US Taxable Bonds | 3.13 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 3.7 |

| US Municipal Bonds | 0.19 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| US HG Bonds | 1.12 | 1.8 | 5.1 | 5.0 |

| US HY Bonds | 0.19 | -0.7 | -0.1 | 0.3 |

| US MMFs | 14.34 | -34.1 | -1.3 | 6.3 |

| UCITS Flows | Feb-24 | 3 mth avg | 2023 avg | 2024 avg |

| Euro MMFs | -15.67 | 16.17 | 15.63 | 7.04 |

| Euro Equities | 12.75 | 5.1 | 0.6 | 6.2 |

| Euro Bonds | 36.95 | 30.6 | 12.3 | 35.9 |

Source: ICI, EPFR, EFAMA, Bloomberg Finance L.P., and J.P. Morgan.

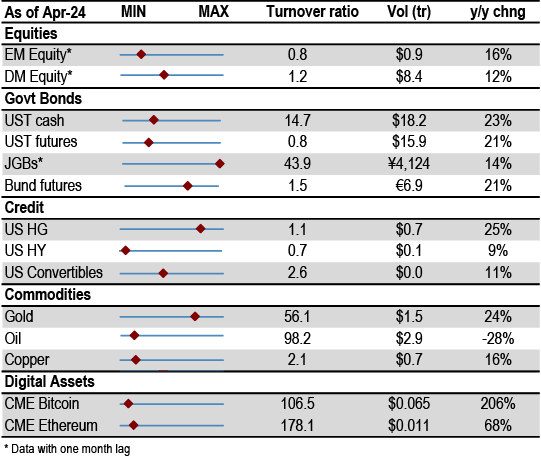

Table A2: Trading turnover monitor

Volumes are monthly and Turnover ratio is annualised (monthly trading volume annualised divided by the amount outstanding). UST Cash is primary dealer transactions in all US government securities. UST futures are from Bloomberg Finance L.P. JGBs are OTC volumes in all Japanese government securities. Bunds, Gold, Oil and Copper are futures. Gold includes Gold ETFs. Min-Max chart is based on Turnover ratio. For Bunds and Commodities, futures trading volumes are used while the outstanding amount is proxied by open interest. The diamond reflects the latest turnover observation. The thin blue line marks the distance between the min and max for the complete time series since Jan-2005 onwards. Y/Y change is change in YTD notional volumes over the same period last year.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., Federal Reserve, Trace, Japan Securities Dealer Association, WFE, J.P. Morgan.

ETF Flow Monitor (as of 8th May)

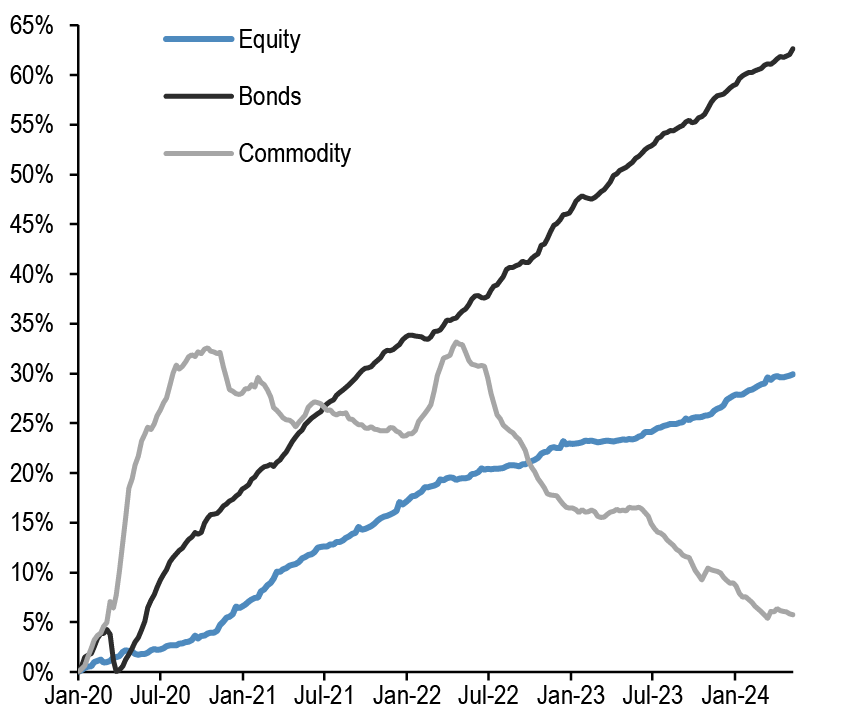

Chart A3: Global Cross Asset ETF Flows

Cumulative flow into ETFs as a % of AUM

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

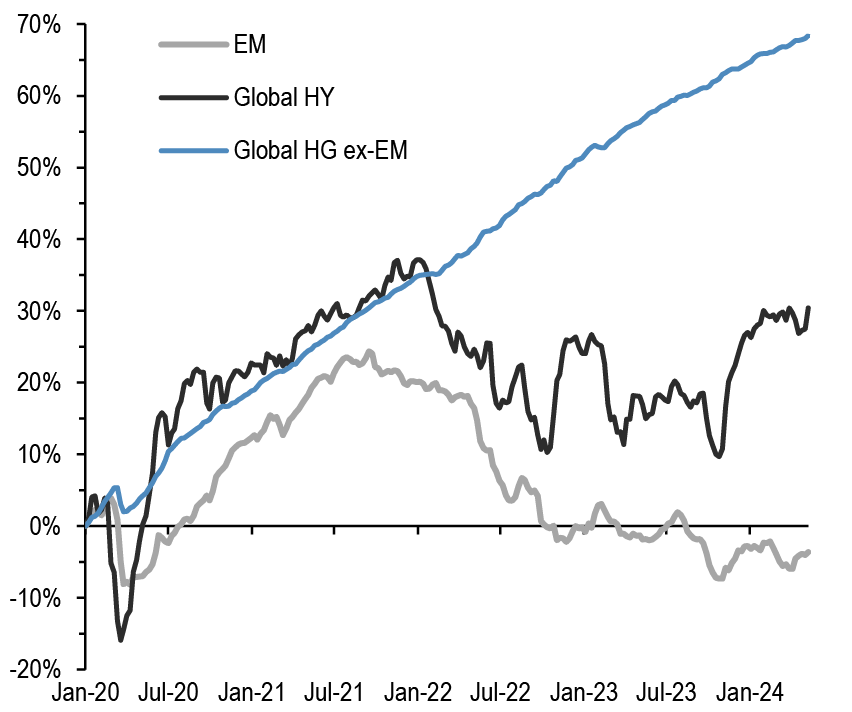

Chart A4: Bond ETF Flows

Cumulative flow into bond ETFs as a % of AUM

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

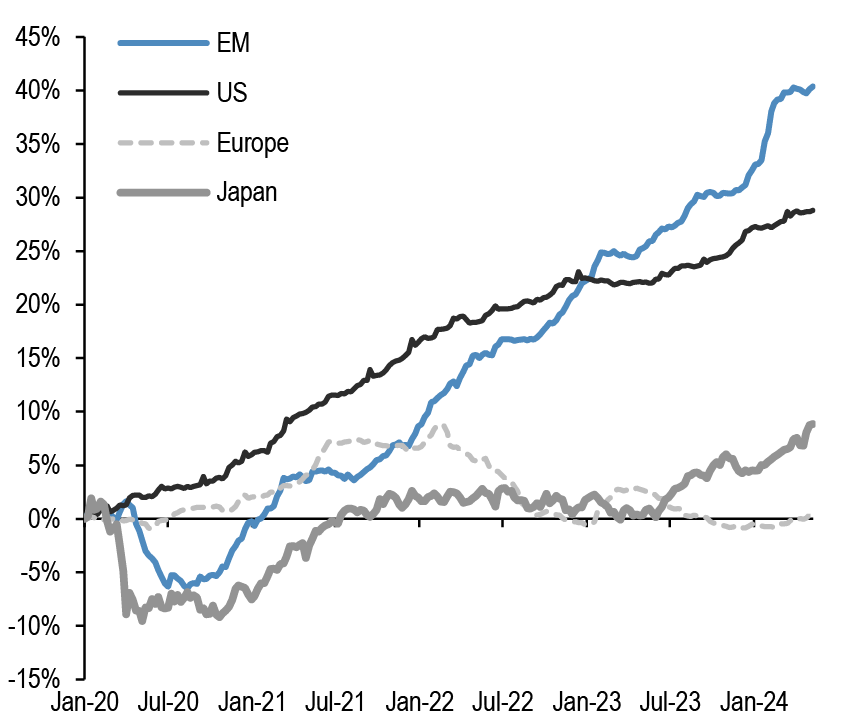

Chart A5: Global Equity ETF Flows

Cumulative flow into global equity ETFs as a % of AUM

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan. Note: We include ETFs with AUM > $200mn in all the flow monitor charts. Chart A5 exclude China On-shore (A-share) ETFs from EM and in Japan. We subtract the BoJ buying of ETFs.

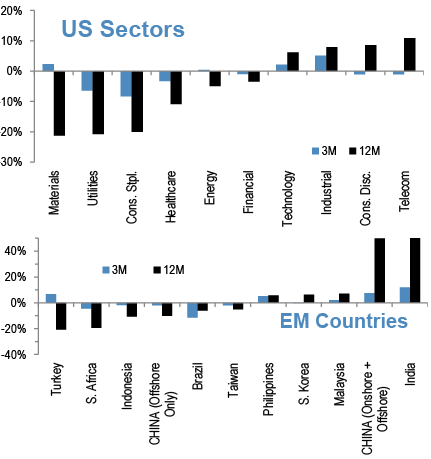

Chart A6: Equity Sectoral and Regional ETF Flows

Rolling 3-month and 12-month change in cumulative flows as a % of AUM. Both sorted by 12-month change

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

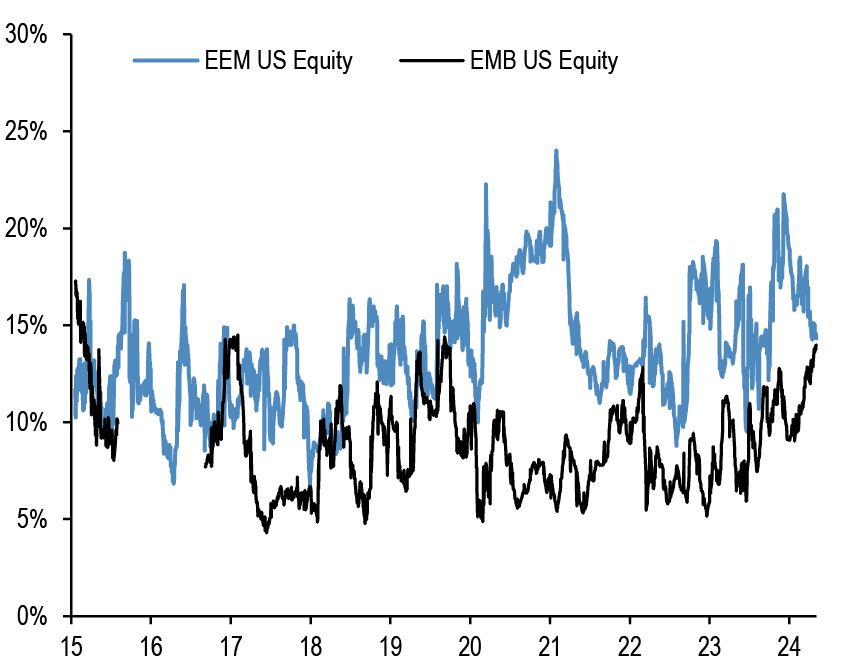

Short Interest Monitor

Chart A7: Short interest on the EEM and EMB US ETF

Short Interest as a % share of share outstanding.

Source: S3, J.P. Morgan

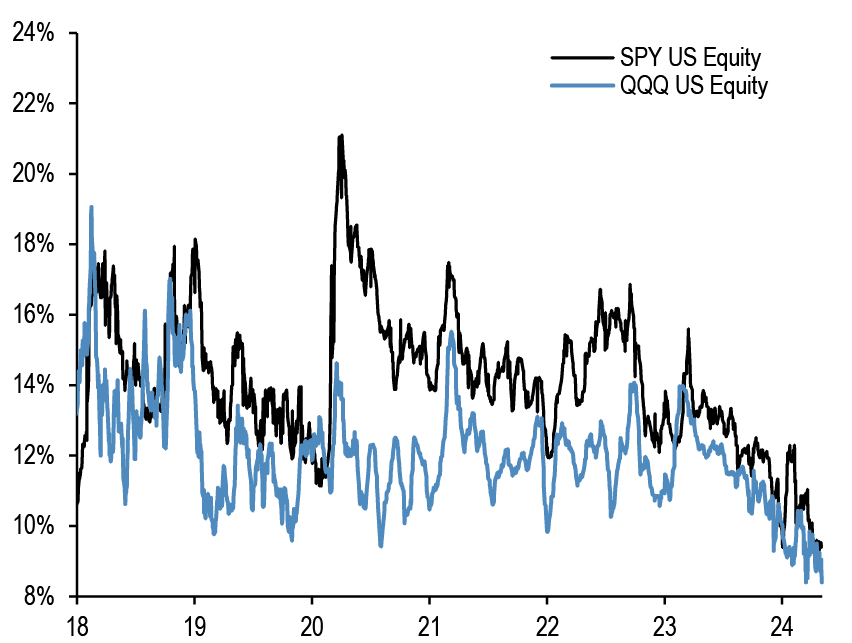

Chart A9: Short interest on the SPY and QQQ US ETF

Short Interest as a % share of share outstanding. Last obs is for 3rd May 2024.

Source: S3, J.P. Morgan

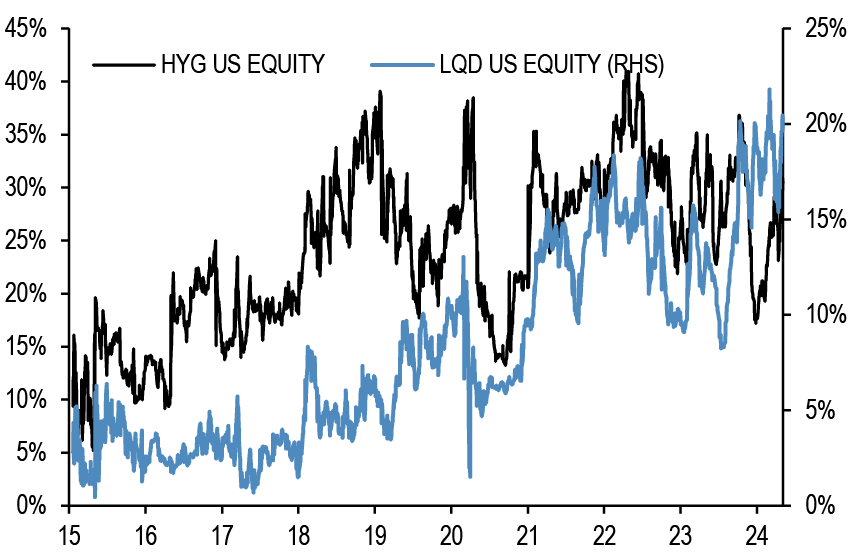

Chart A8: Short interest on the LQD and HYG US ETF

Short Interest as a % share of share outstanding.

Source: S3, J.P. Morgan

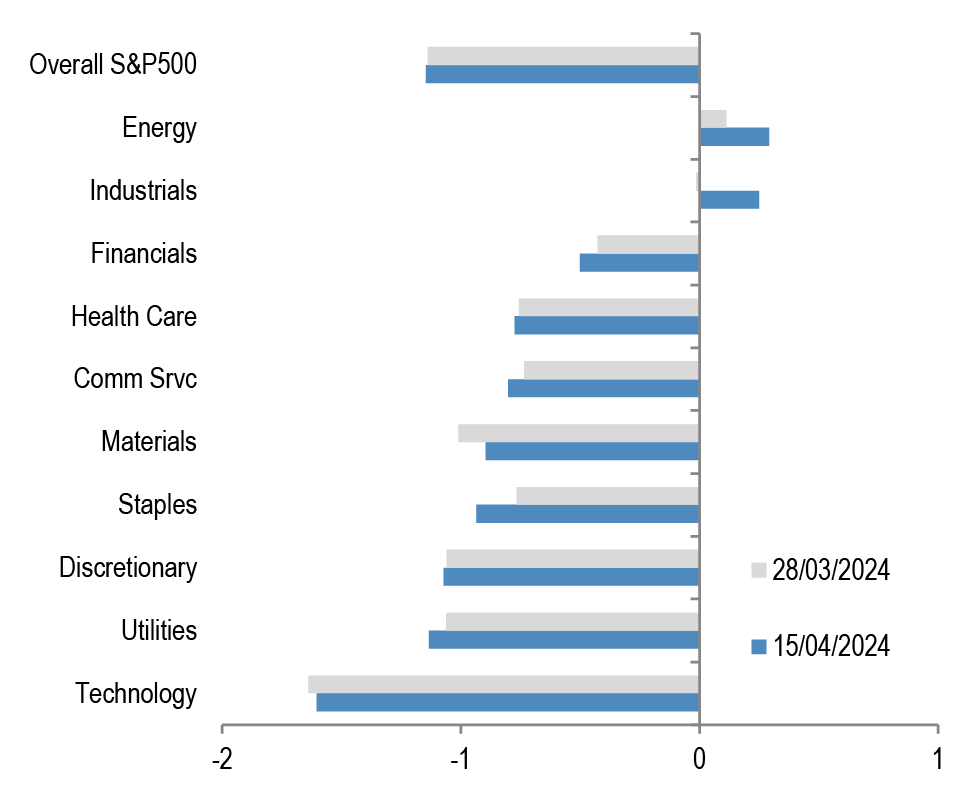

Chart A10: S&P500 sector short interest

Short interest as a % of shares outstanding based on z-scores. A strategy which overweights the S&P500 sectors with the highest short interest z-score (as % of shares o/s) vs. those with the lowest, produced an information ratio of 0.7 with a success rate of 56% (see F&L, Jun 28,2013 for more details).

Source: NYSE, Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan

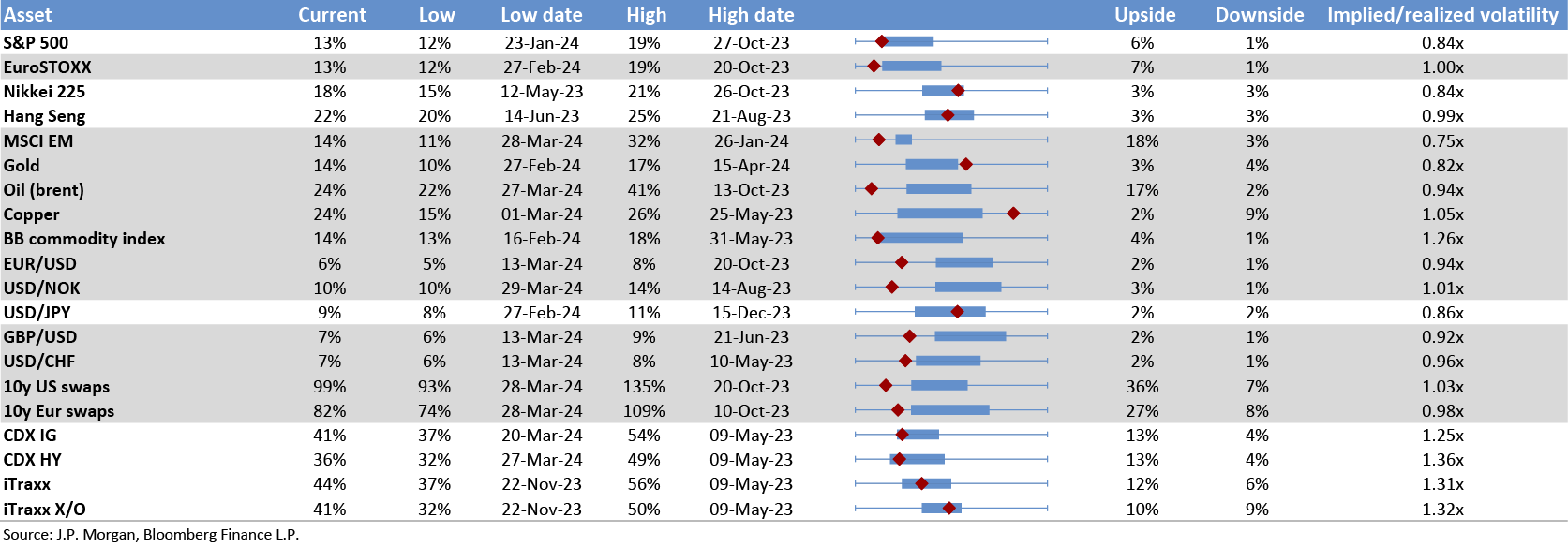

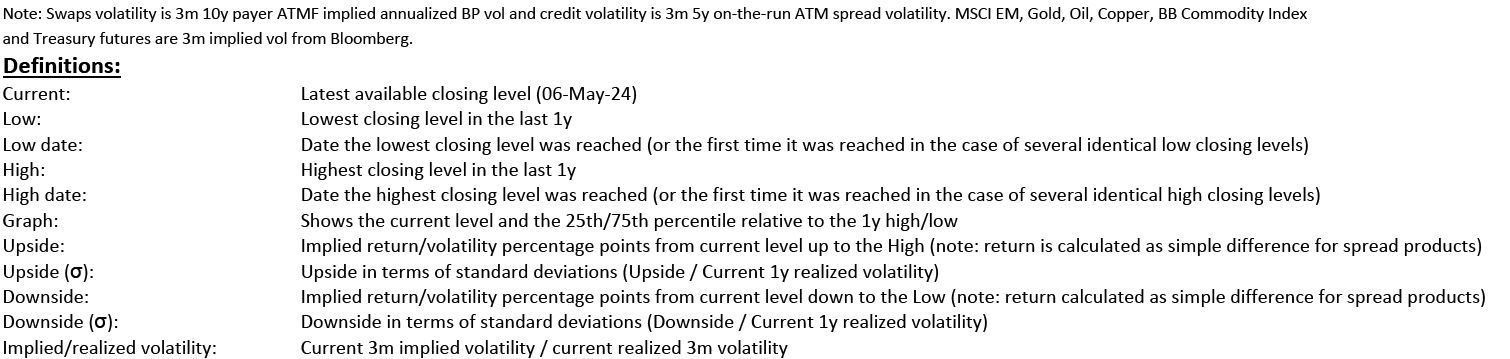

Chart A11a: Cross Asset Volatility Monitor 3m ATM Implied Volatility (1y history) as of 7th May-2024

This table shows the richness/cheapness of current three-month implied volatility levels (red dot) against their one-year historical range (thin blue bar) and the ratio to current realised volatility. Assets with implied volatility outside their 25th/75th percentile range (thick blue bar) are highlighted. The implied-to-realised volatility ratio uses 3-month implied volatilities and 1-month (around 21 trading days) realised volatilities for each asset.

Chart A11b: Option skew monitor

Skew is the difference between the implied volatility of out-of-the-money (OTM) call options and put options. A positive skew implies more demand for calls than puts and a negative skew, higher demand for puts than calls. It can therefore be seen as an indicator of risk perception in that a highly negative skew inequities is indicative of a bearish view. The chart shows z-score of the skew, i.e. the skew minus a rolling 2-year avg skew divided by a rolling two-year standard deviation of the skew. A negative skew on iTraxx Main means investors favour buying protection, i.e. a short risk position. A positive skew for the Bund reflects a long duration view, also a short risk position.

Source: J.P. Morgan.

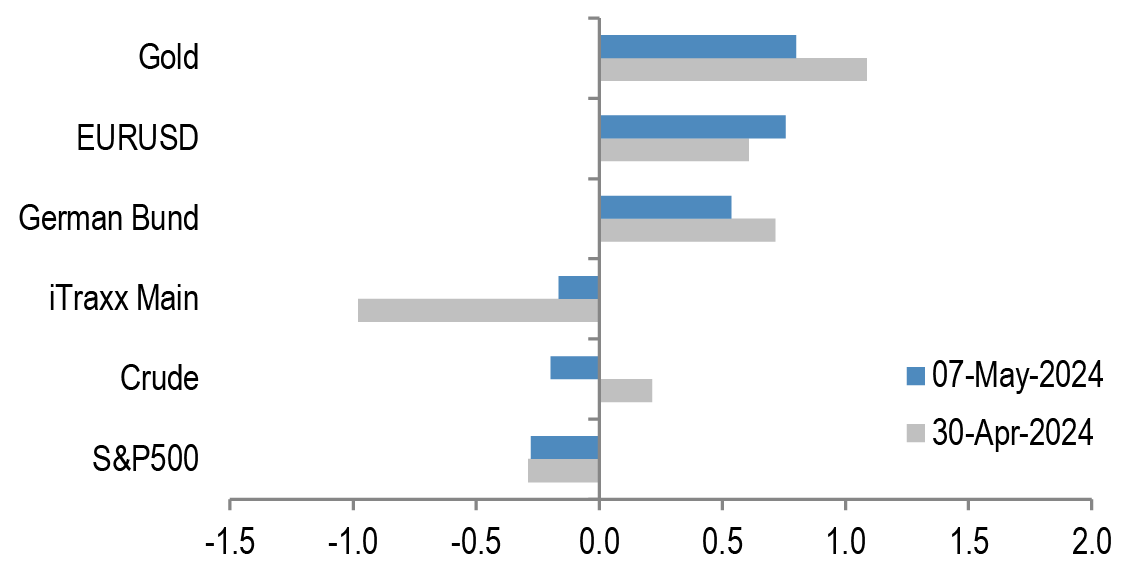

Chart A11c: Equity-Bond metric map

Explanation of Equity - Bond metric map: Each of the five axes corresponds to a key indicator for markets. The position of the blue line on each axis shows how far the current observation is from the extremes at either end of the scale. For example, a reading at the centre for value would mean that risky assets are the most expensive they have ever been while a reading at the other end of the axis would mean they are the cheapest they have ever been. Overall, the larger the blue area within the pentagon, the better for the risky markets. All variables are expressed as the percentile of the distribution that the observation falls into. I.e. a reading in the middle of the axis means that the observation falls exactly at the median of all historical observations. Value: The slope of the risk-return trade-off line calculated across USTs, US HG and HY corporate bonds and US equities(see GMOS p. 6, Loeys et al, Jul 6 2011 for more details). Positions: Difference between net spec positions on US equities and intermediate sector UST. See Chart A13. Flow momentum: The difference between flows into equity funds (incl. ETFs) and flows into bond funds. Chart A1. We then smooth this using a Hodrick-Prescott filter with a lambda parameter of 100. We then take the weekly change in this smoothed series as shown in Chart A1. Economic momentum:The 2-month change in the global manufacturing PMI. (See REVISITING: Using the Global PMI as trading signal, Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou, Jan 2012). Equity price momentum: The 6-month change in the S&P500 equity index. As of 3rd May 24.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

Spec position monitor

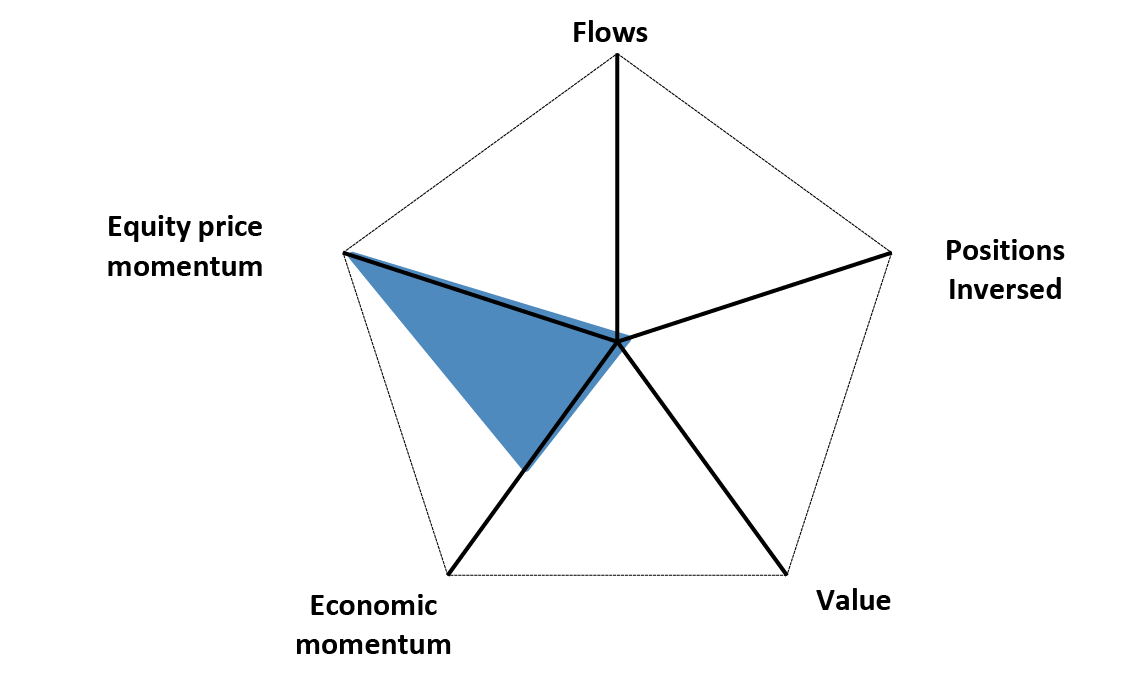

Chart A12: Weekly Spec Position Monitor

Net spec positions are proxied by the number of long contracts minus the number of short contracts using the speculative category of the Commitments of Traders reports (as reported by CFTC). To proxy for speculative investors for equity and US Treasury bond futures positions we use Asset managers and leveraged funds (see Chart A13), whereas for other assets we use the legacy Non-Commercial category. This net position is then converted to a dollar amount by multiplying by the contract size and then the corresponding futures price. We then scale the net positions by open interest. The chart shows the z-score of these net positions. US rates is a duration-weighted composite of the individual UST futures contracts excluding the Eurodollar contract.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., CFTC, J.P. Morgan

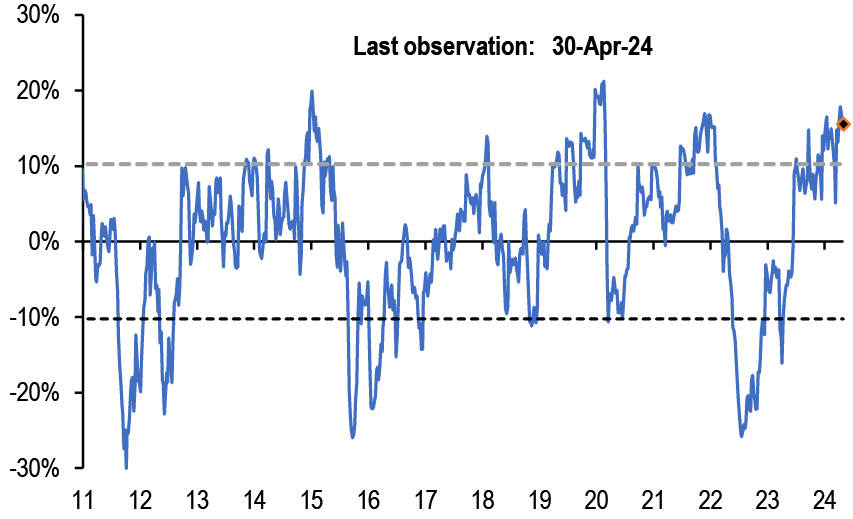

Chart A14: Spec position indicator on Risky vs. Safe currencies

Difference between net spec positions on risky & safe currencies. Net spec position is calculated in USD across 5 ‘risky’ and 3 ‘safe’ currencies (safe currencies also include Gold). These positions are then scaled by open interest and we take an average of ‘risky’ and ‘safe’ assets to create two series. The chart is then simply the difference between the“risky” and “safe” series. The final series shown in the chart below is demeaned using data since 2006. The risky currencies are: AUD, NZD,CAD, RUB, MXN and BRL. The safe currencies are: JPY, CHF and Gold.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., CFTC, J.P. Morgan.

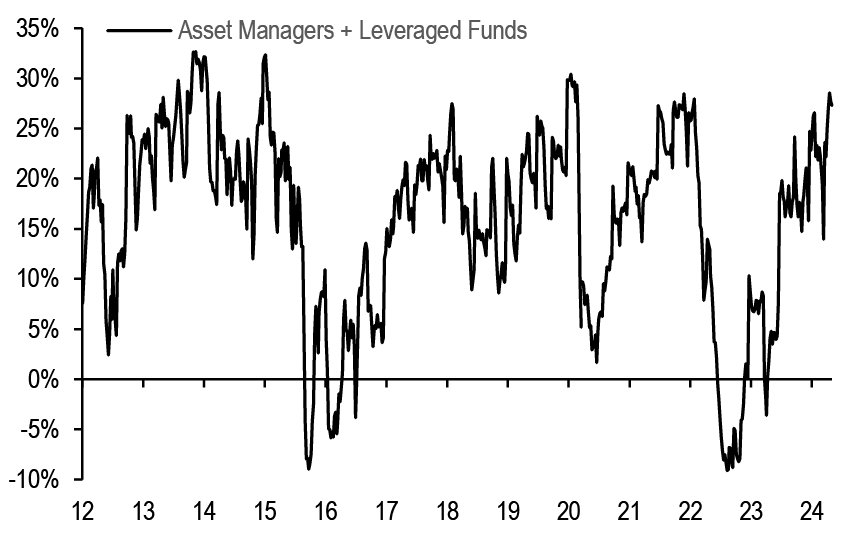

Chart A13: Positions in US equity futures by Asset managers and Leveraged funds

CFTC positions in US equity futures by Leveraged funds and Asset managers (as a % of open interest). It is an aggregate of the S&P500, DowJones, NASDAQ and their Mini futures contracts.

Source: CFTC, Bloomberg Finance L.P. and J.P. Morgan

Chart A15: Spec position indicator on US equity futures vs. intermediate sector UST futures

Difference between net spec positions on US equity futures vs.intermediate sector UST futures. This indicator is derived by the difference between total CFTC positions in US equity futures by Asset managers + Leveraged Funds scaled by open interest minus the Asset managers + Leveraged Funds spec position on intermediate sector UST futures (i.e. all UST futures duration weighted ex ED and ex 2Y UST futures) also scaled by open interest.

Source: CFTC, Bloomberg Finance L.P. and J.P. Morgan

Mutual fund and hedge fund betas

Chart A16: 21-day rolling beta of 20 biggest active US bond mutual fund managers with respect to the US Agg Bond Index

The dotted line shows the average beta since 2013.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

Chart A17: 21-day rolling beta of 20 biggest active Euro bond mutual fund managers with respect to the Euro Agg Bond Index

The dotted line shows the average beta since 2013.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

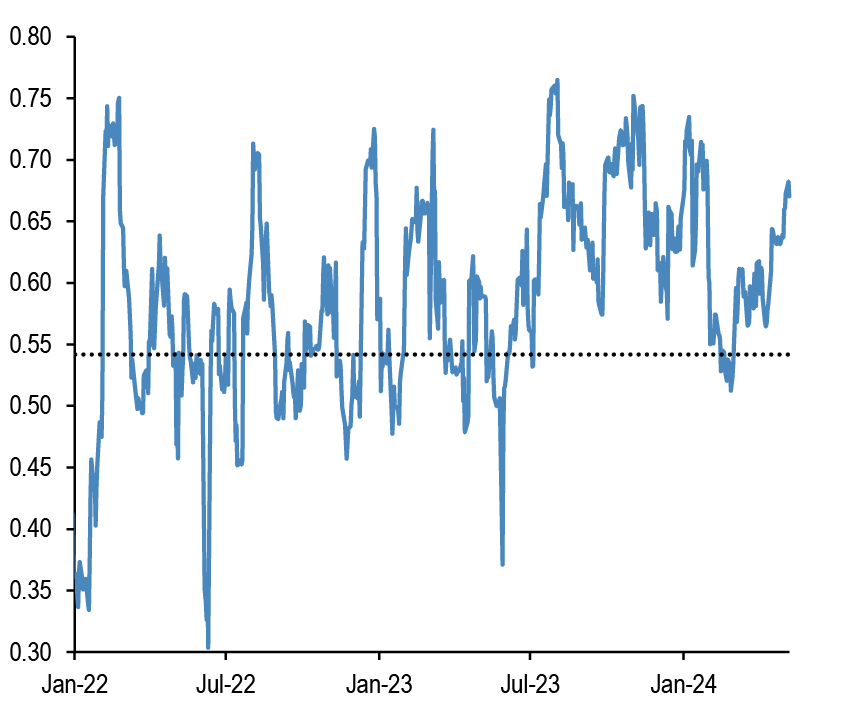

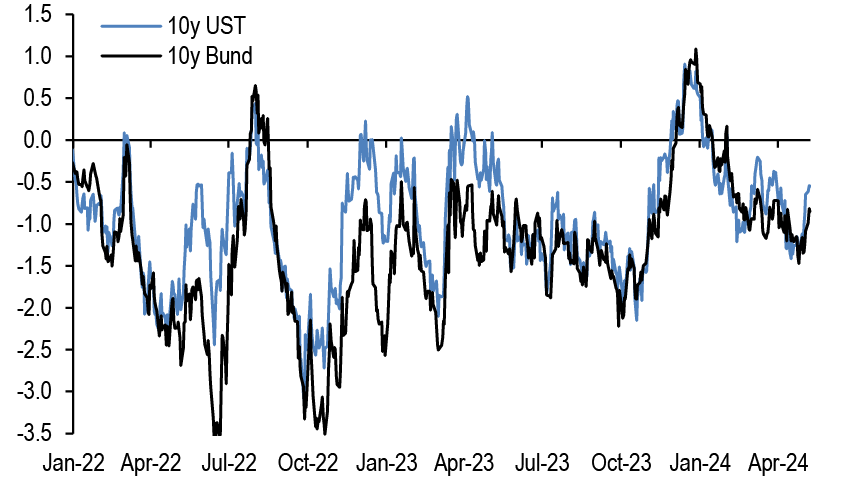

Chart A18: Performance of various type of investors

The table depicts the performance of various types of investors in % as of 6th May 2024.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., HFR, Pivotal Path, J.P. Morgan.

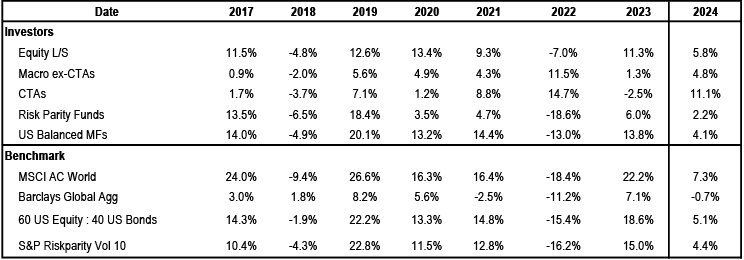

Chart A19: Momentum signals for 10Y UST and 10Y Bunds

Average z-score of Short- and Long-term momentum signal in our Trend Following Strategy framework shown in Tables A3 and A4 below in the Appendix

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

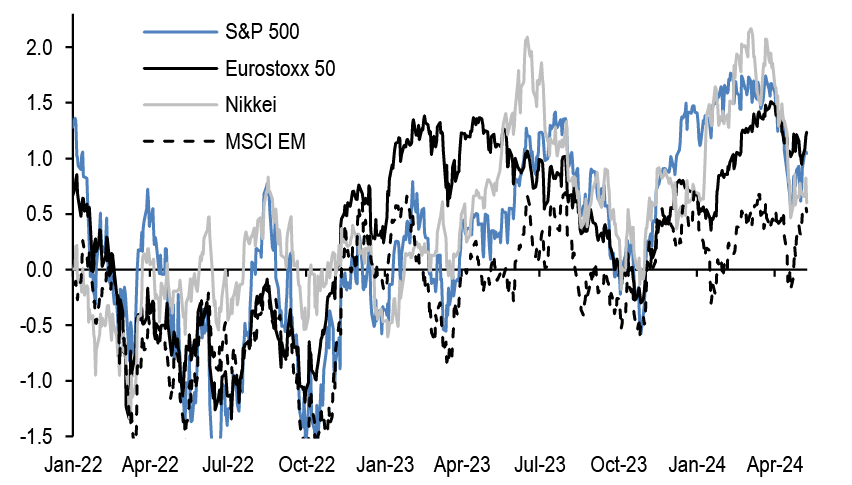

Chart A20: Momentum signals for S&P500

Average z-score of Short- and Long-term momentum signal in our Trend Following Strategy framework shown in Tables A3 and A4 below in the Appendix.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

Chart A21: Equity beta of US Balanced Mutual funds and Risk Parity funds

Rolling 21-day equity beta based on a bivariate regression of the daily returns of our Balanced Mutual fund and Risk Parity fund return indices to the daily returns of the S&P 500 and BarCap US Agg indices. Given that these funds invest in both equities and bonds we believe that the bivariate regression will be more suitable for these funds. Our risk parity index consists of 25 daily reporting Risk Parity funds. Our Balanced Mutual fund index includes the top 20 US-based active funds by assets and that have existed since 2006. Our Balanced Mutual fund index has a total AUM of$700bn, which is around half of the total AUM of $1.5tr of US based Balanced funds which we believe to be a good proxy of the overall industry It excludes tracker funds and funds with a low tracking error. Dotted lines are average since 2015.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

Chart A22: Equity beta of monthly reporting Equity Long/Short hedge funds

Proxied by the ratio of the monthly performance of Pivotal Path Asset-Weighted Equity Hedge fund index divided by the monthly performance of MSCI ACWorld Index.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., Pivotal Path, J.P. Morgan

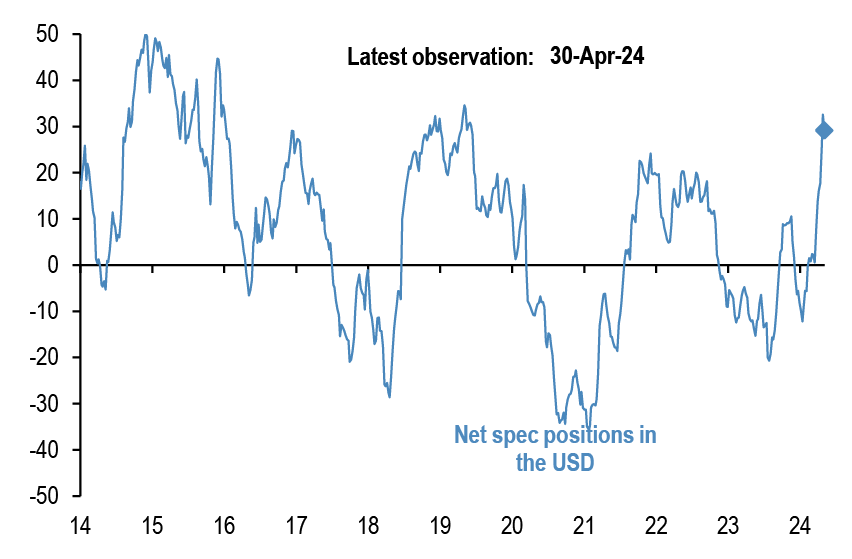

Chart A23: USD exposure of currency hedge funds

The net spec position in the USD as reported by the CFTC. Spec is the non-commercial category from the CFTC.

Source: CFTC, Barclay, Datastream, Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

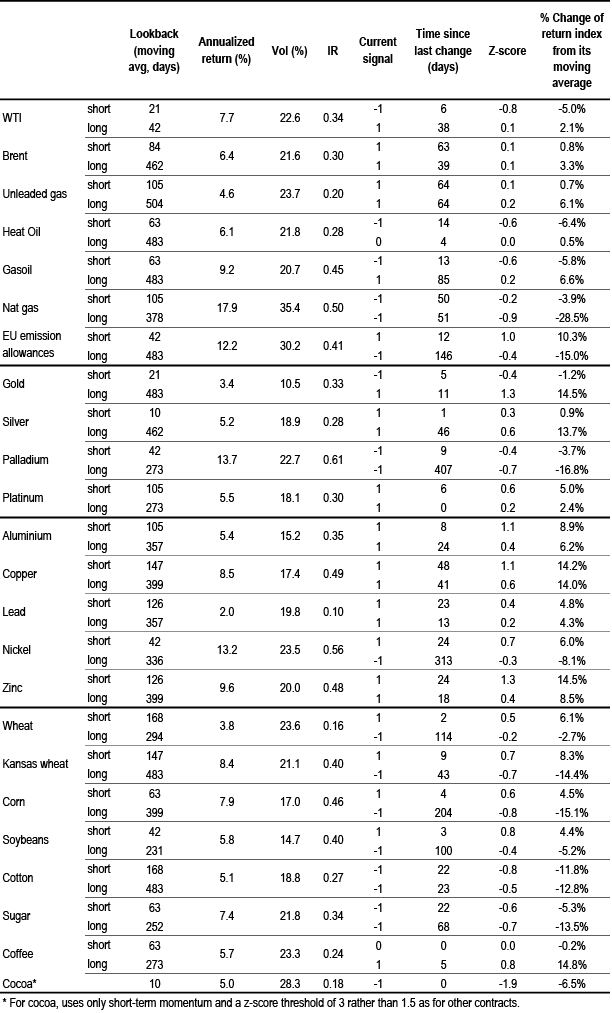

CTAs – Trend following investors’ momentum indicators

Table A3: Simple return momentum trading rules across various commodities

Optimal lookback period of each momentum strategy combined with a mean reversion indicator that turns signal neutral when momentum z-score more than 1.5 standard deviations above or below mean, and a filter that turns neutral when the z-score is low (below 0.05 and above -0.05) to avoid excessive trading. Lookbacks, current signals and z-scores are shown for shorter-term and longer-term momentum separately, along with performance of a combined signal. Annualized return, volatility and

information ratio of the signal; current signal; and z-score of the current return over the relevant lookback period; data from 1999 onward.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan calculations.

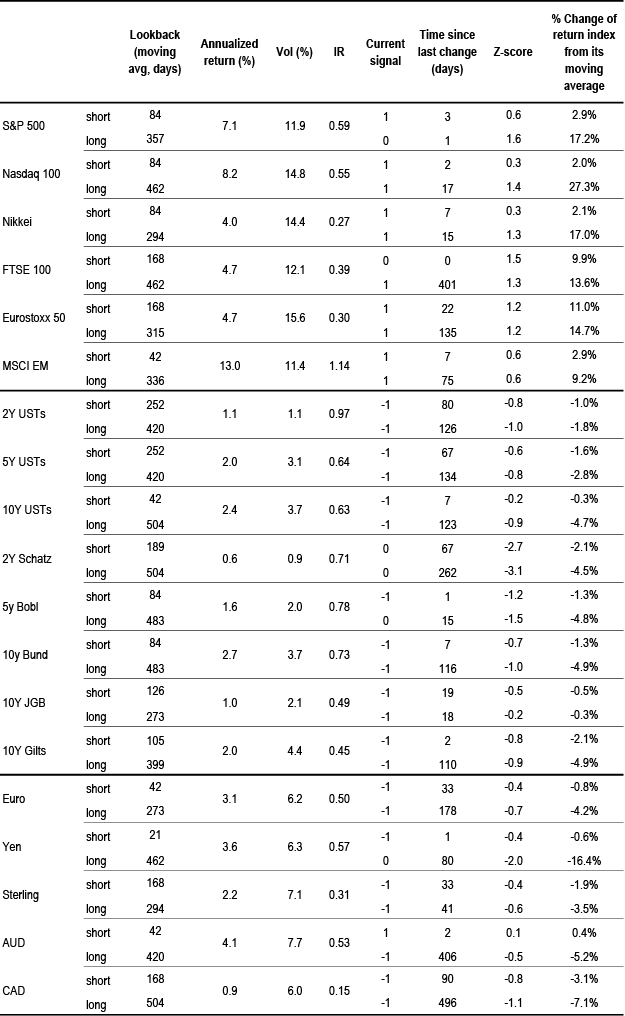

Table A4: Simple return momentum trading rules across international equity indices, bond futures and FX

Optimal lookback period of each momentum strategy combined with a mean reversion indicator that turns signal neutral when momentum z-score more than 1.5 standard deviations above or below mean, and a filter that turns neutral when the z-score is low (below 0.05 and above -0.05) to avoid excessive trading. Lookbacks, current signals and z-scores are shown for shorter-term and longer-term momentum separately, along with performance of a combined signal. Annualized return, volatility and

information ratio of the signal; current signal; and z-score of the current return over the relevant lookback period; data from 1999 onward.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan calculations.

Corporate Activity

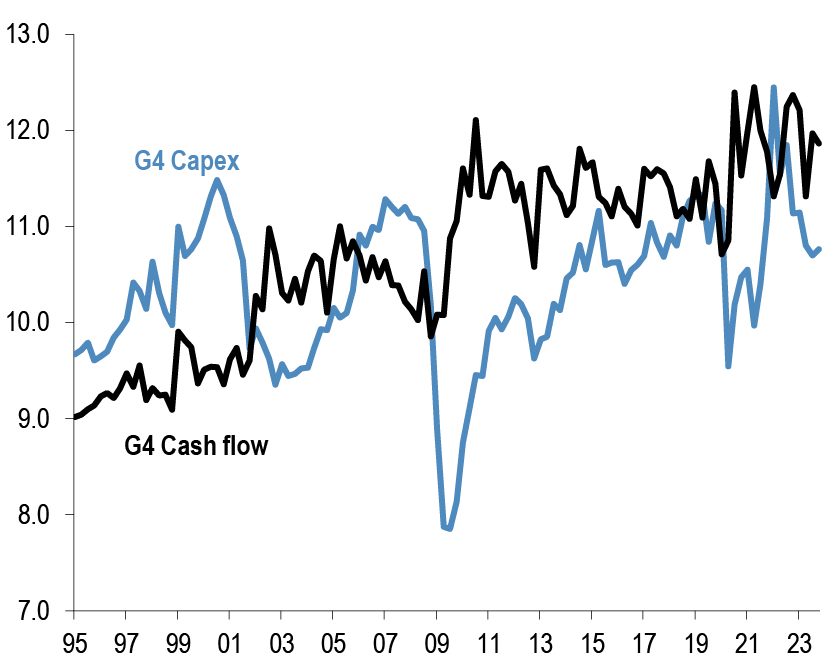

Chart A24: G4 non-financial corporate capex and cash flow as % of GDP

% of GDP, G4 includes the US, the UK, the Euro area and Japan. Last observation as of Q4 2023.

Source: ECB, BOJ, BOE, Federal Reserve flow of funds, J.P. Morgan.

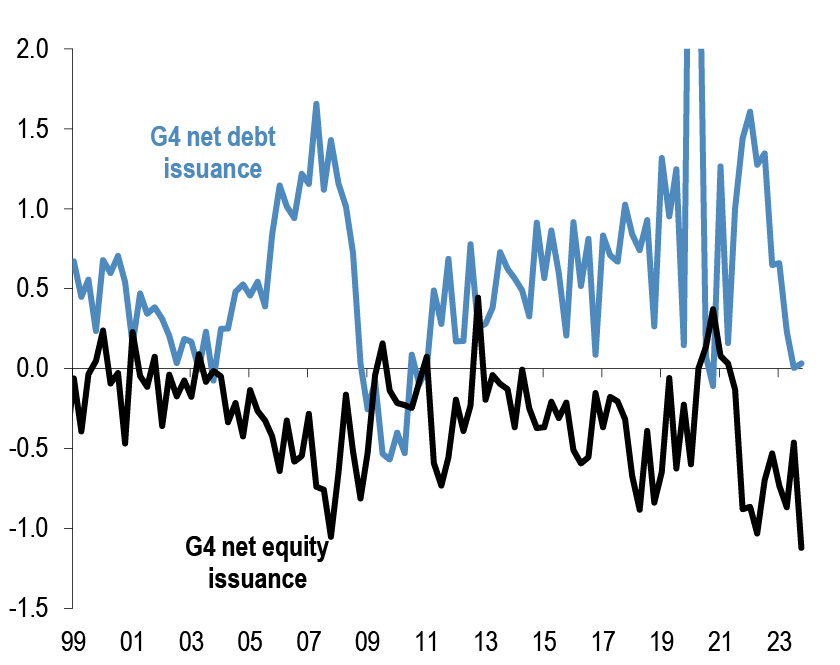

Chart A25: G4 non-financial corporate sector net debt and equity issuance

$tr per quarter, G4 includes the US, the UK, the Euro area and Japan. Last observation as of Q4 2023.

Source: ECB, BOJ, BOE, Federal Reserve flow of funds, J.P. Morgan.

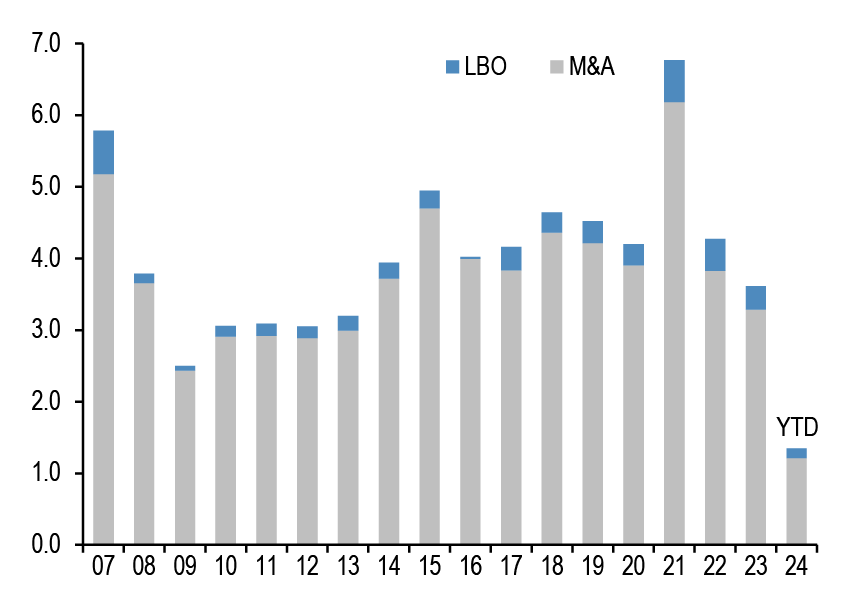

Chart A26: Global M&A and LBO

$tr. M&A and LBOs are announced.

Source: Dealogic, J.P. Morgan.

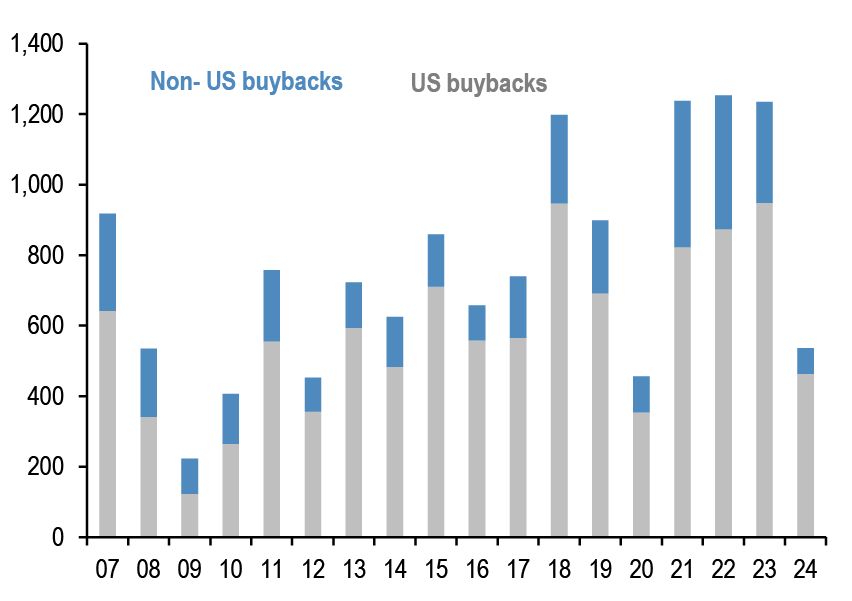

Chart A27: US and non-US share buyback

$bn, are as of Apr’24. Buybacks are announced.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., Thomson Reuters, J.P. Morgan

Pension fund and insurance company flows

Chart A28: G4 pension funds and insurance companies equity and bond flows

Equity and bond buying in $bn per quarter. G4 includes the US, the UK,Euro area and Japan. Last observation is Q4 2023.

Source: ECB, BOJ, BOE, Federal Reserve flow of funds, J.P. Morgan.

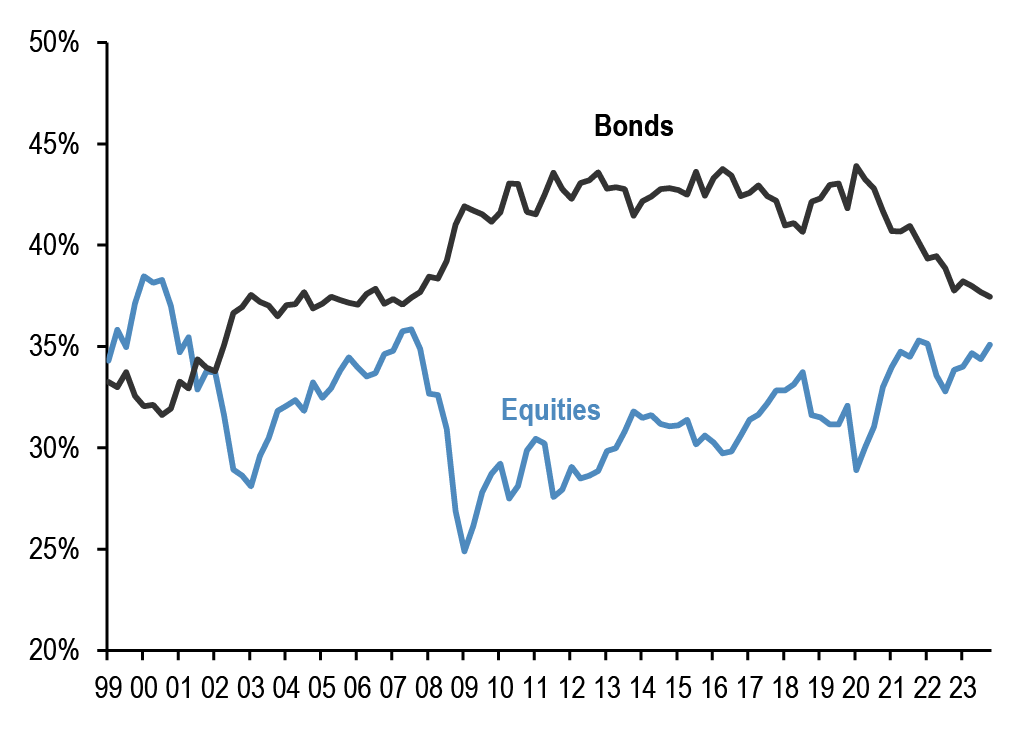

Chart A29: G4 pension funds and insurance companies equity and bond levels

Equity and bond as % of total assets per quarter. G4 includes the US, the UK, Euro area and Japan. Last observation is Q4 2023.

Source: ECB, BOJ, BOE, Federal Reserve flow of funds., J.P. Morgan

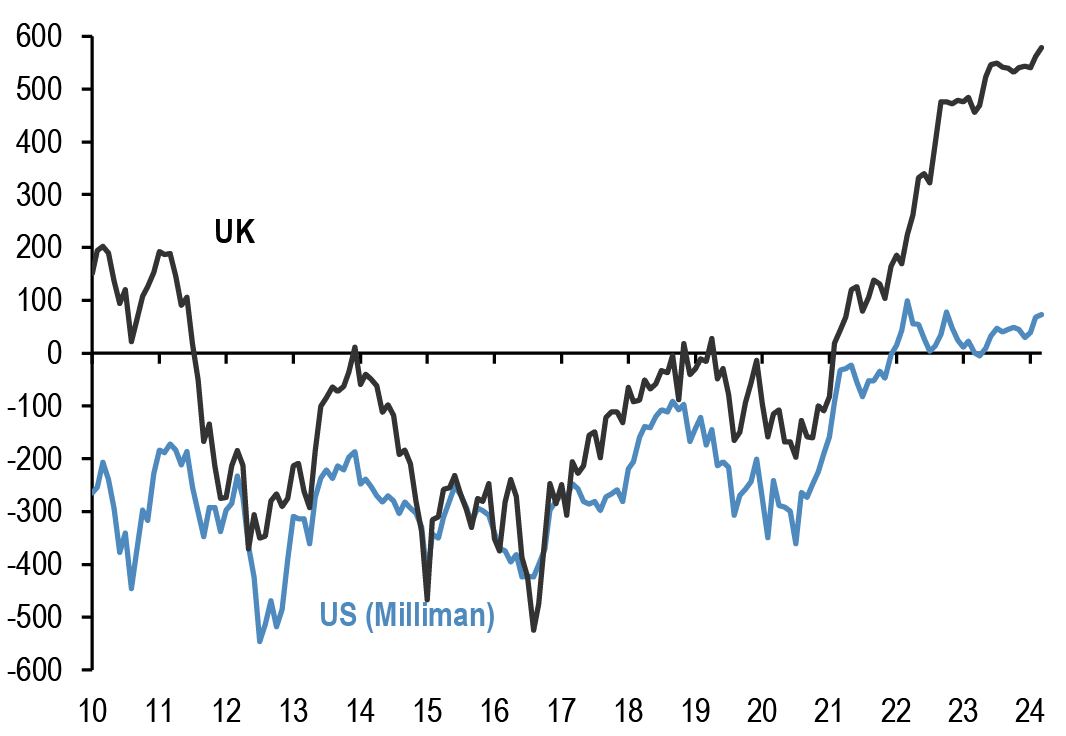

Chart A30: Pension fund deficits

US$bn. For US, funded status of the 100 largest corporate defined benefit pension plans, from Milliman. For UK, funded status of the defined benefit schemes eligible for entry to the Pension Protection Fund, converted to US$at today’s exchange rates.

Last obs. is Mar’24 for US & UK.

Source: Milliman, UK Pension Protection Fund, J.P. Morgan.

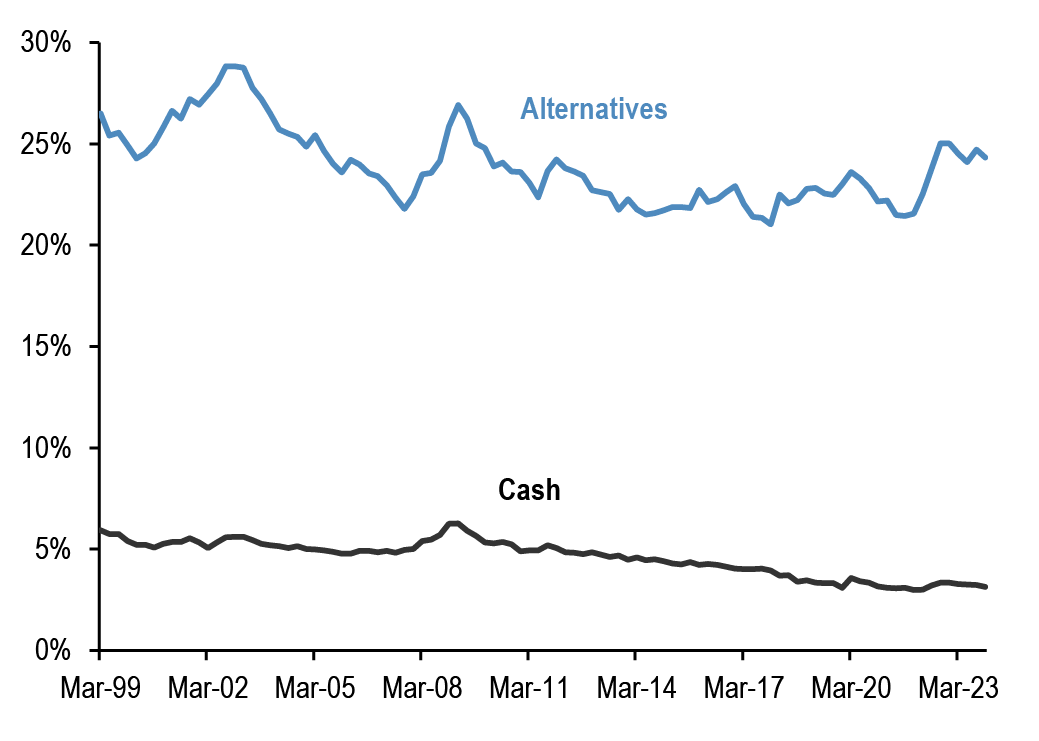

Chart A31: G4 pension funds and insurance companies cash and alternatives levels

Cash and alternative investments as % of total assets per quarter. G4 includes the US, the UK, Euro area and Japan. Last observation is Q4 2023.

Source: ECB, BOJ, BOE, Federal Reserve flow of funds, J.P. Morgan.

Credit Creation

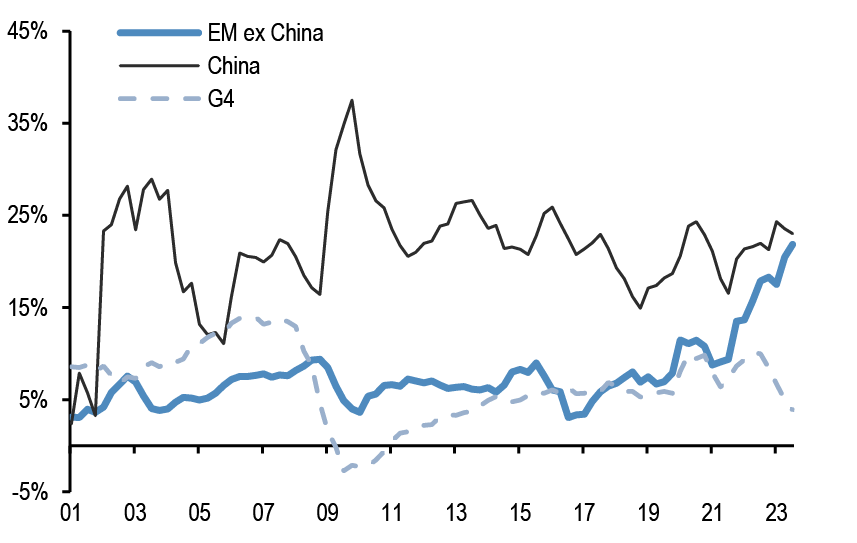

Chart A32: Credit creation in the US, Japan and Euro area

Rolling sum of 4-quarter credit creation as % of GDP. Credit creation includes both bank loans as well as net debt issuance by non-financial corporations and households. Last obs. is Q4’23 for US, Japan, & Euro Area.

Source: Fed, ECB, BoJ, Bloomberg Finance L.P., and J.P. Morgan calculations.

Chart A33: Credit creation in EM

Rolling sum of 4-quarter credit creation as % of GDP. Credit creation includes both bank loans as well as net debt issuance by non-financial corporations and households. Last obs. is for Q3’23.

Source: G4 Central banks FoF, BIS, ICI, Barcap, Bloomberg Finance L.P., IMF, and J.P.Morgan calculation

Chart A34: Monthly net issuance of US HG bonds

$bn. May 2024.

Source: Dealogic, J.P. Morgan

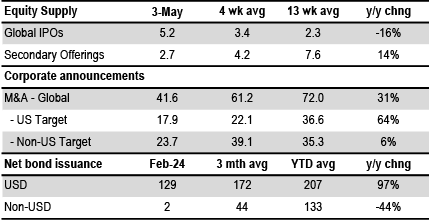

Table A5: Equity and Bond issuance

$bn, Equity supply and corporate announcements are based on announced deals, not completed. M&A is announced deal value and buybacks are announced transactions. Y/Y change is change in YTD announcements over the same period last year.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., Dealogic, Thomson Reuters, J.P. Morgan.

Bitcoin monitor

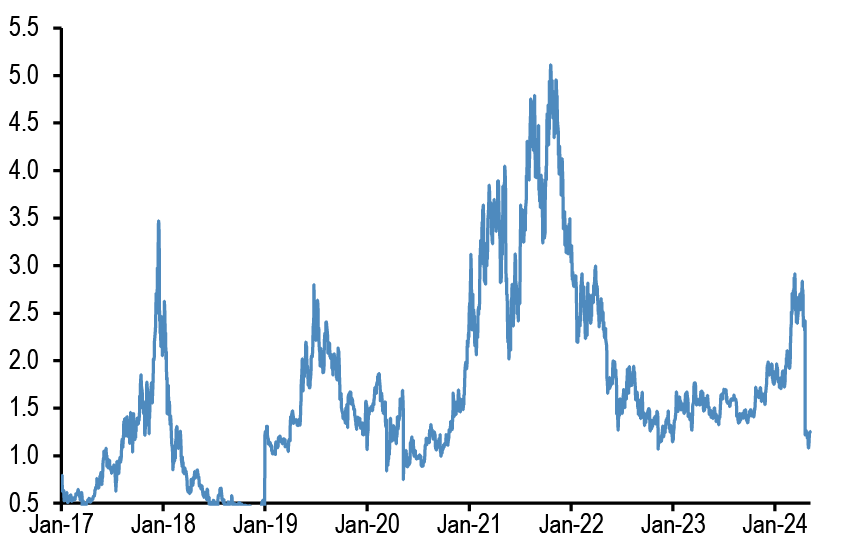

Chart A35: Our Bitcoin position proxy based on open interest in CME Bitcoin futures contracts

In number of contracts. Last obs. for 7th May 2024.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan

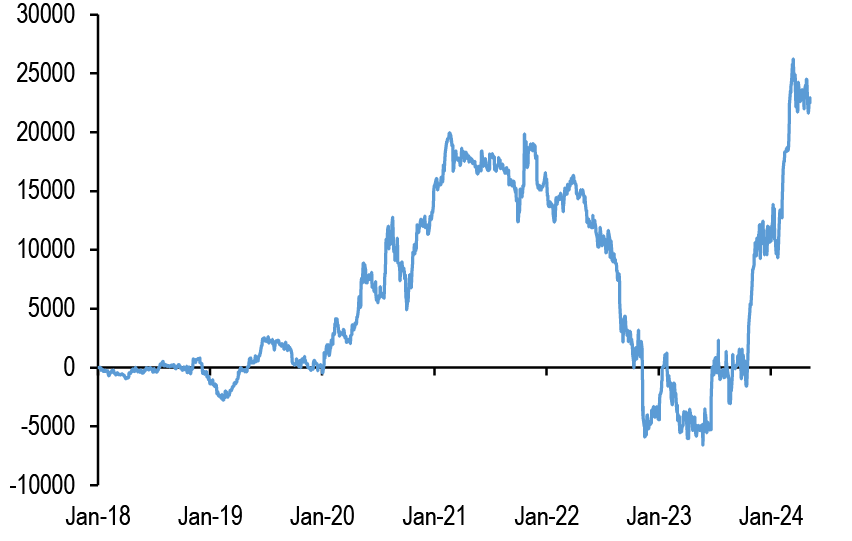

Chart A36: Cumulative Flows in all Bitcoin funds and Gold ETF holdings

Both the y-axis in $bn.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

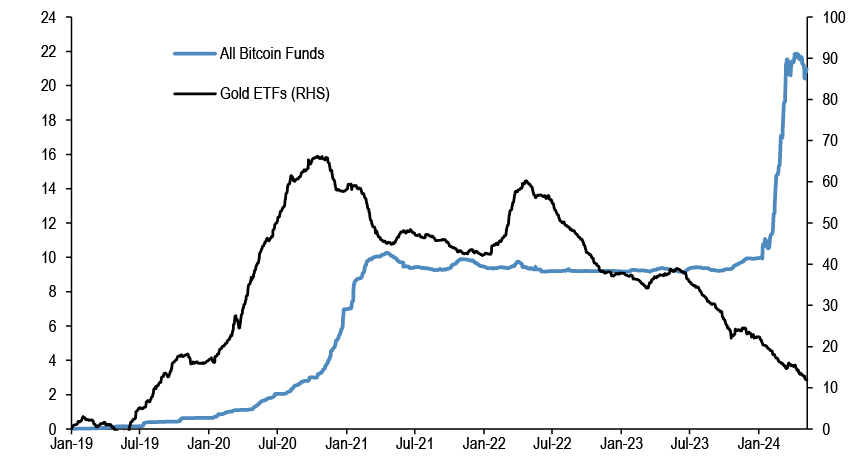

Chart A37: Ratio of Bitcoin market price to production cost

Based on the cost of production approach following Hayes (2018).

Source: Bitinfocharts, J.P. Morgan

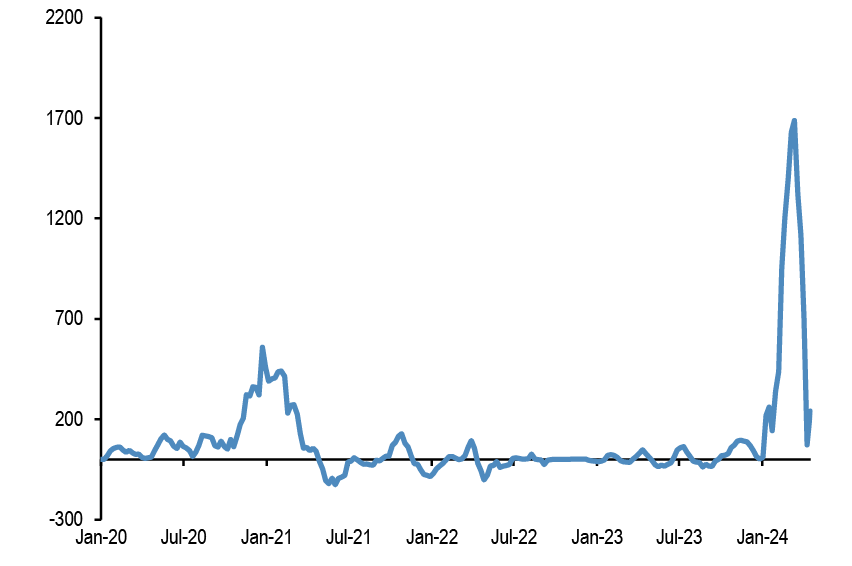

Chart A38: Flow pace into publicly-listed Bitcoin funds including Bitcoin ETFs

$mm per week, 4-week rolling average flow.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

Japanese flows and positions

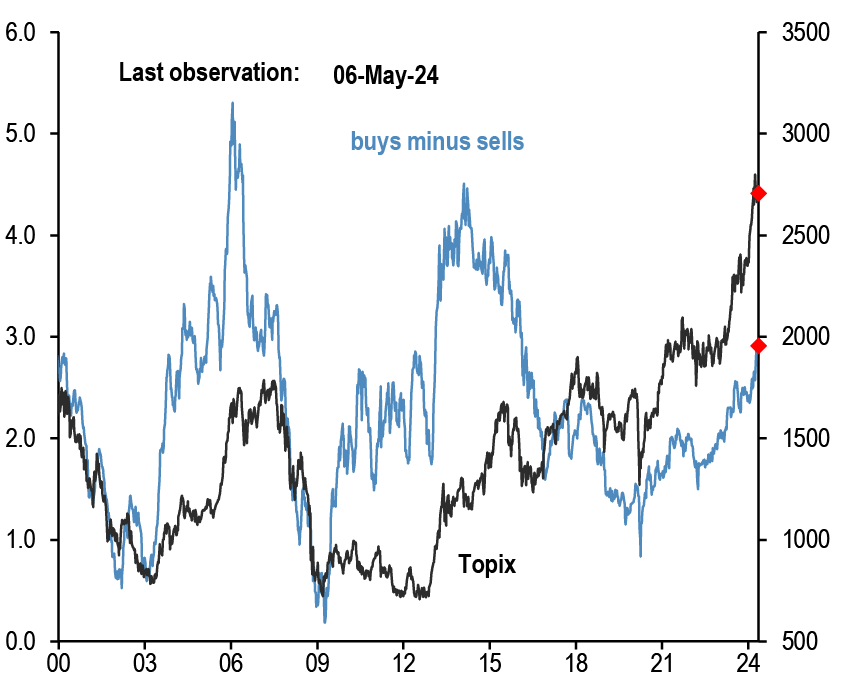

Chart A39: Tokyo Stock Exchange margin trading: total buys minus total sells

In bn of shares. Topix on right axis.

Source: Tokyo Stock Exchange, Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

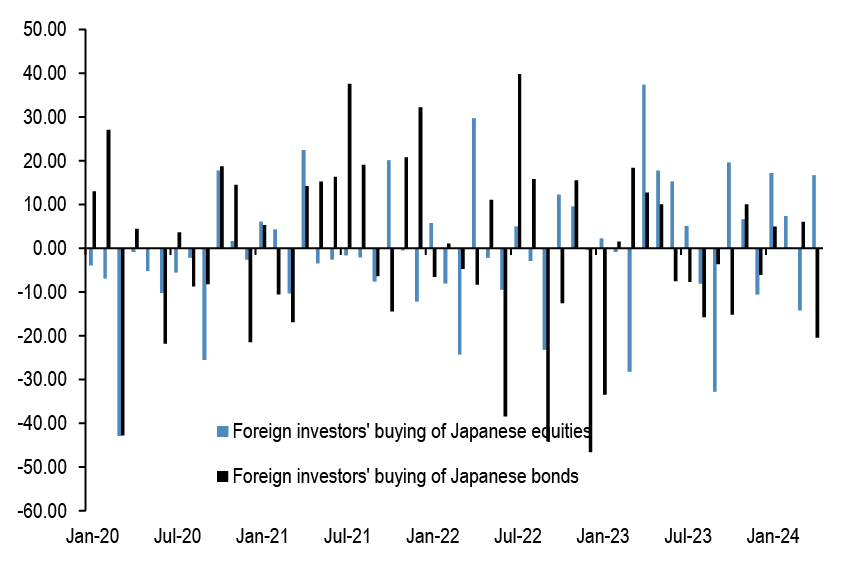

Chart A40: Monthly net purchases of Japanese bonds and Japanese equities by foreign residents

$bn, Last weekly obs. is for 26th Apr’ 24.

Source: Japan MoF, Bloomberg Finance L.P., and J.P. Morgan.

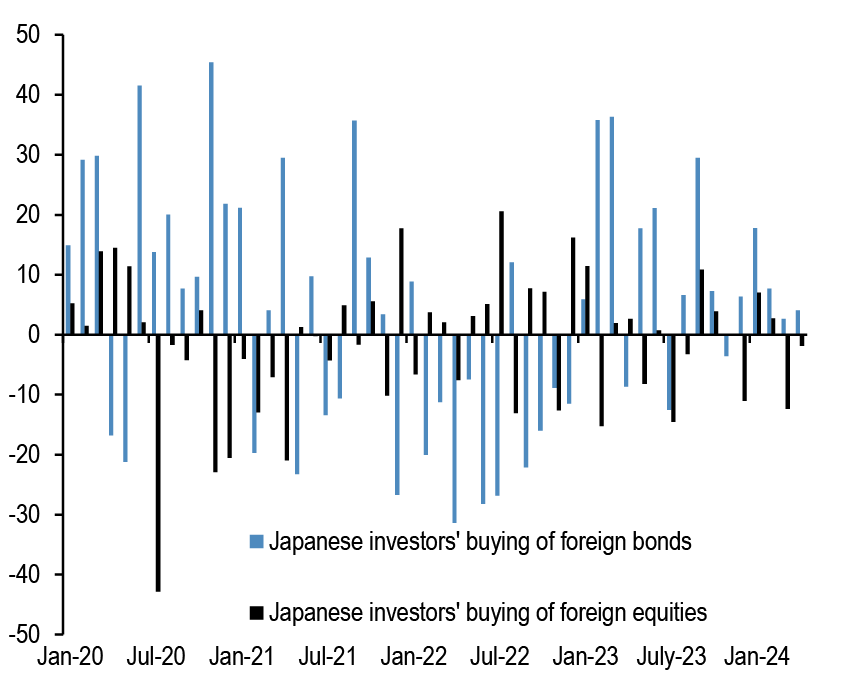

Chart A41: Monthly net purchases of foreign bonds and foreign equities by Japanese residents

$bn, Last weekly obs. is for 26th Apr’ 24.

Source: Japan MoF, Bloomberg Finance L.P., and J.P. Morgan.

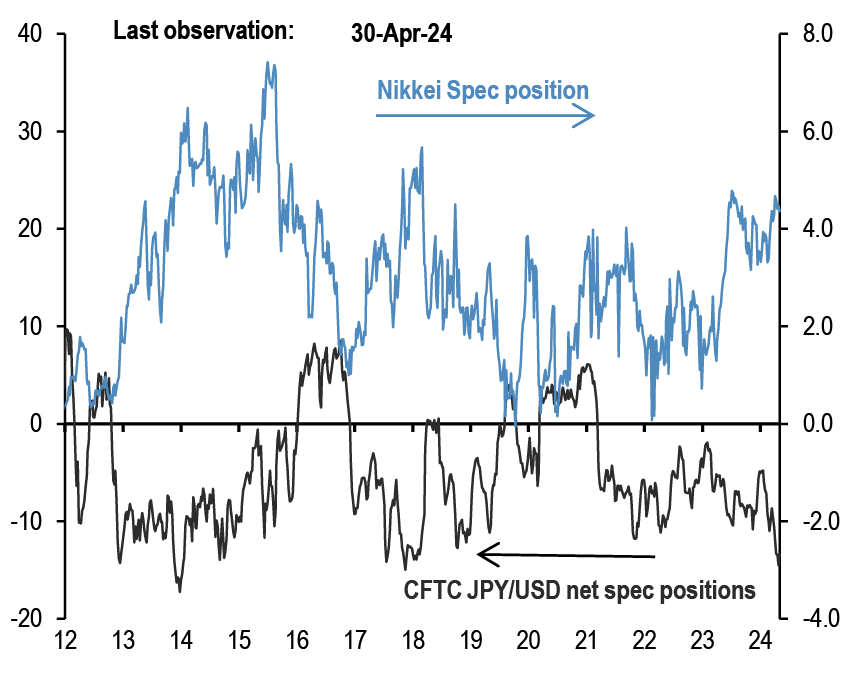

Chart A42: Overseas CFTC spec positions

CFTC spec positions are in $bn. For Nikkei we use CFTC positions in Nikkei futures (USD & JPY) by Leveraged funds and Asset managers.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., CFTC, J.P. Morgan calculations.

Commodity flows and positions

Chart A43: Gold spec positions

$bn. CFTC net long minus short position in futures for the Managed Money category.

Source: CFTC, Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

Chart A44: Gold ETFs

Mn troy oz. Physical gold held by all gold ETFs globally.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

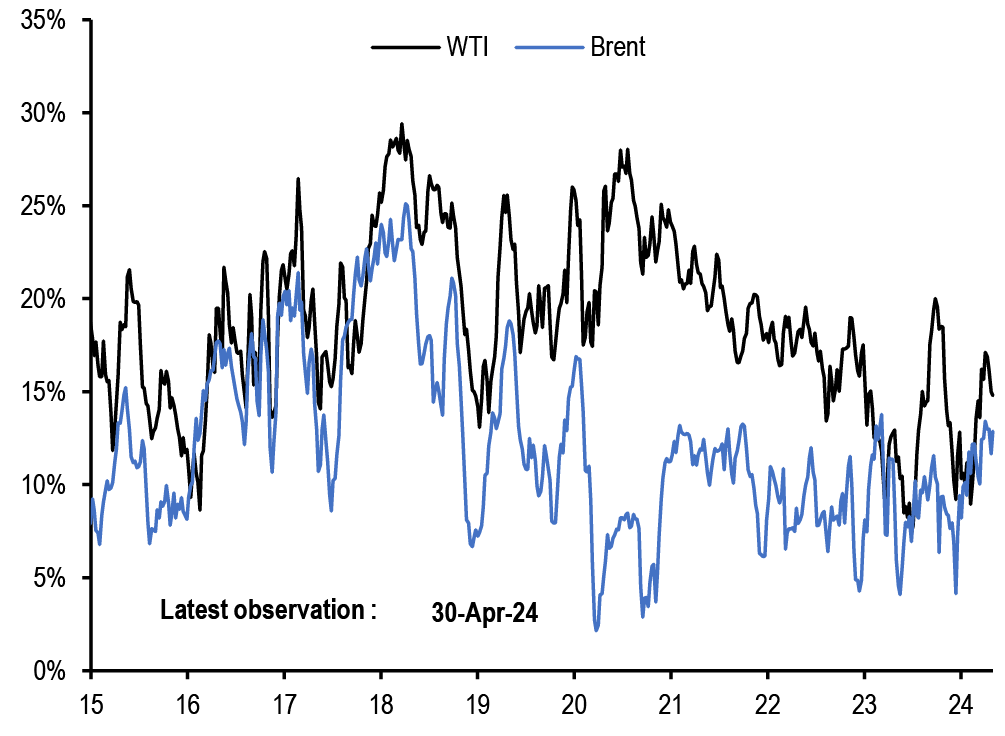

Chart A45: Oil spec positions

Net spec positions divided by open interest. CFTC futures positions for WTI and Brent are net long minus short for the Managed Money category.

Source: CFTC, Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

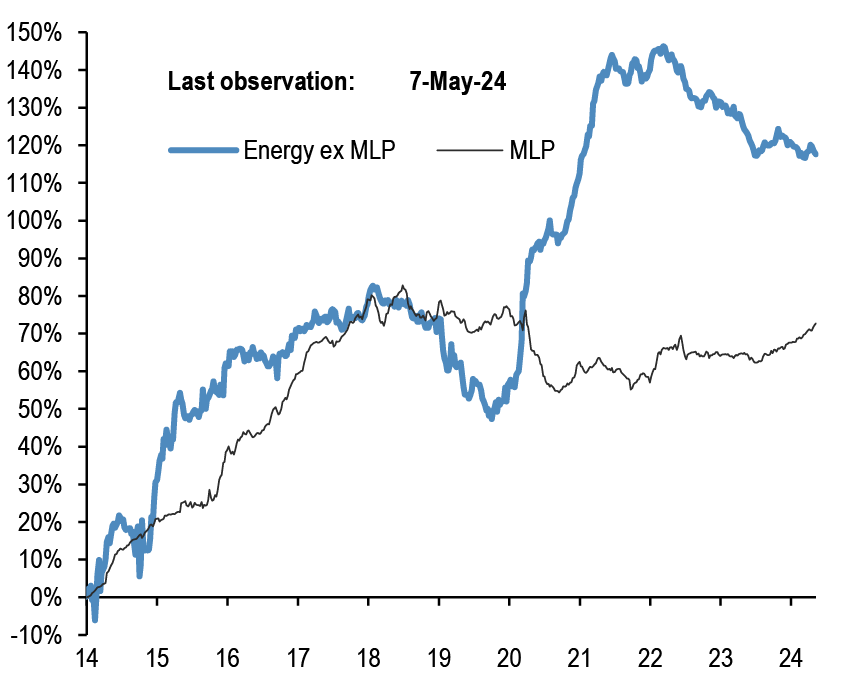

Chart A46: Energy ETF flows

Cumulative energy ETFs flow as a % of AUM. MLP refers to the Alerian MLP ETF.

Source: CFTC, Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan.

Corporate FX hedging proxies

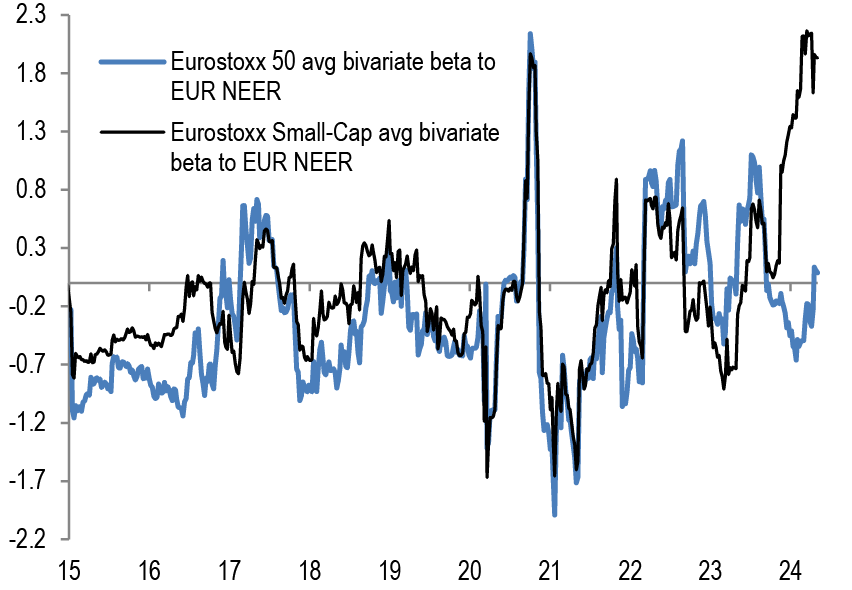

Chart A47: Average beta of Eurostoxx 50 companies and Eurostoxx Small-Cap to trade-weighted EUR

Rolling 26 weeks average betas based on a bivariate regression of the weekly returns of individual stocks in the Eurostoxx 50 index to the weekly returns of the MSCI AC World and JPM EUR Nominal broad effective exchange rate (NEER).

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan

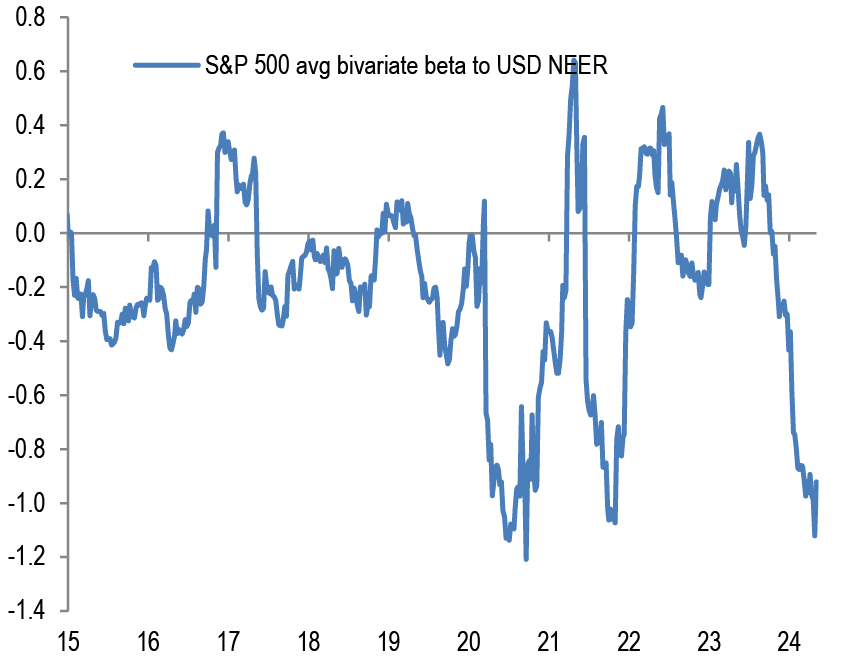

Chart A48: Average beta of S&P500 companies to trade-weighted US dollar

Rolling 26 weeks average betas based on a bivariate regression of the weekly returns of stocks in the S&P500 index to the weekly returns of the MSCI AC World and JPM USD Nominal broad effective exchange rate(NEER).

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan

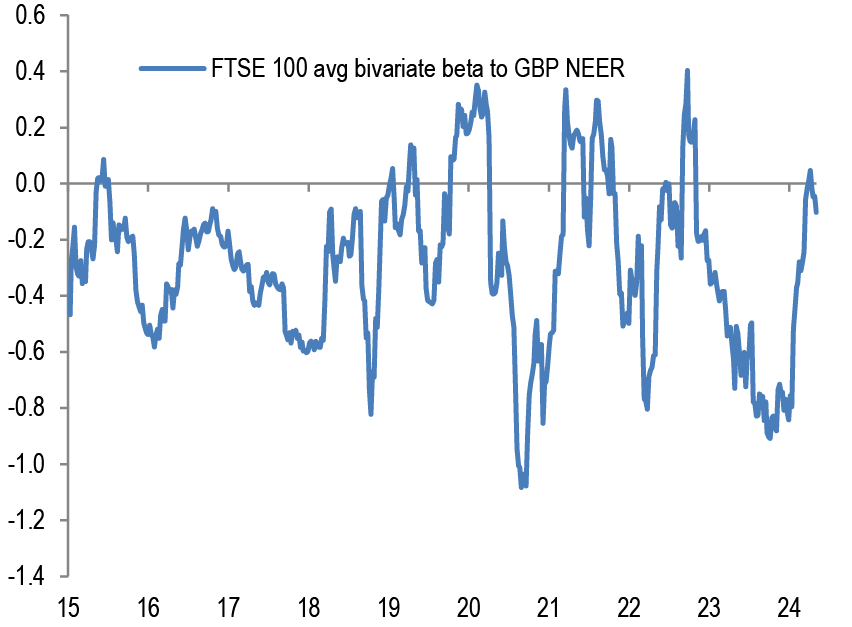

Chart A49: Average beta of FTSE 100 companies to trade-weighted GBP

Rolling 26 weeks average betas based on a bivariate regression of the weekly returns of individual stocks in the FTSE 100 index to the weekly returns of the MSCI AC World and JPM GBP Nominal broad effective exchange rate (NEER).

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan

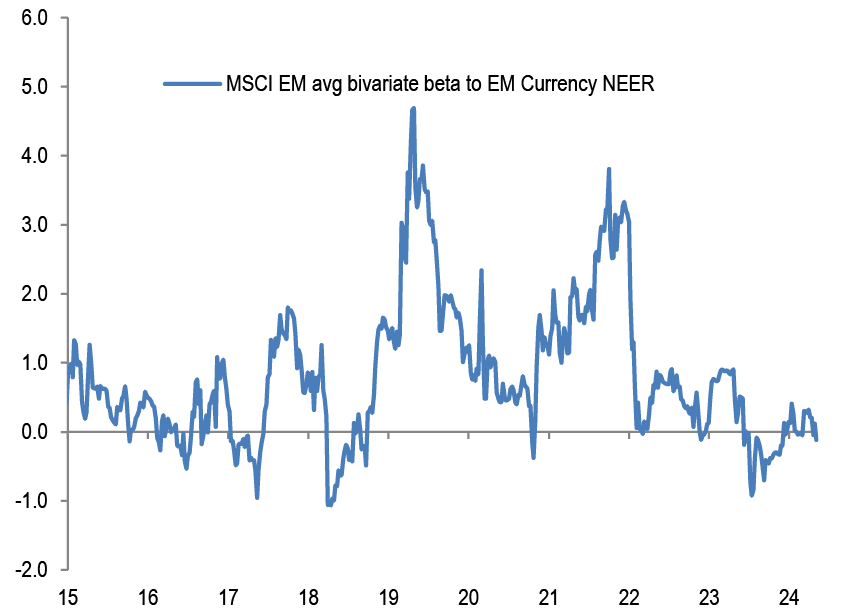

Chart A50: Average beta of MSCI EM companies to trade-weighted EM Currency Index

Rolling 26 weeks average betas based on a bivariate regression of the weekly returns of individual stocks in the MSCI EM index to the weekly returns of the MSCI AC World and JPM EM Nominal broad effective exchange rate (NEER).

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan

Non-Bank investors’ implied allocations

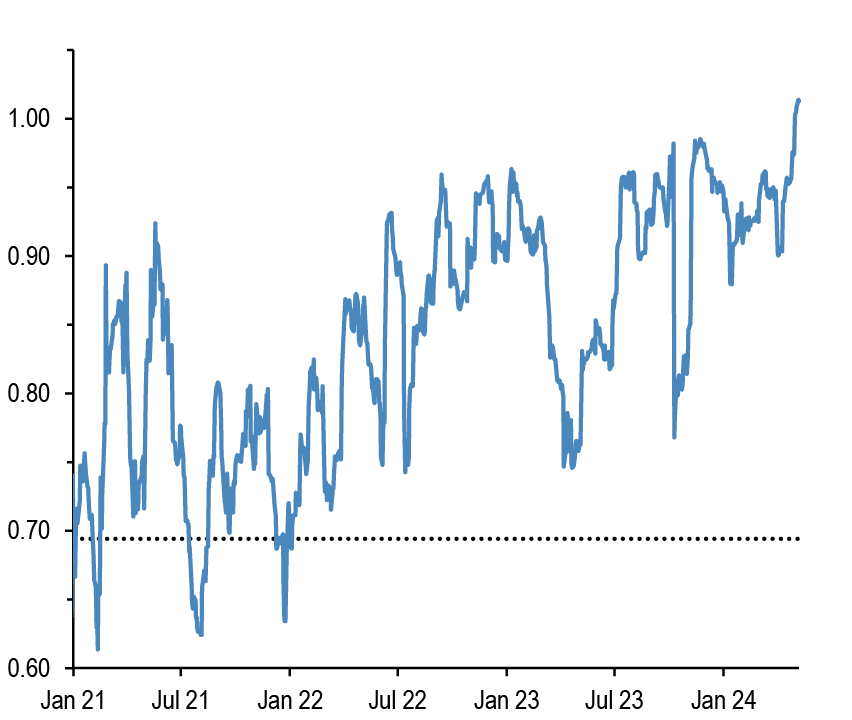

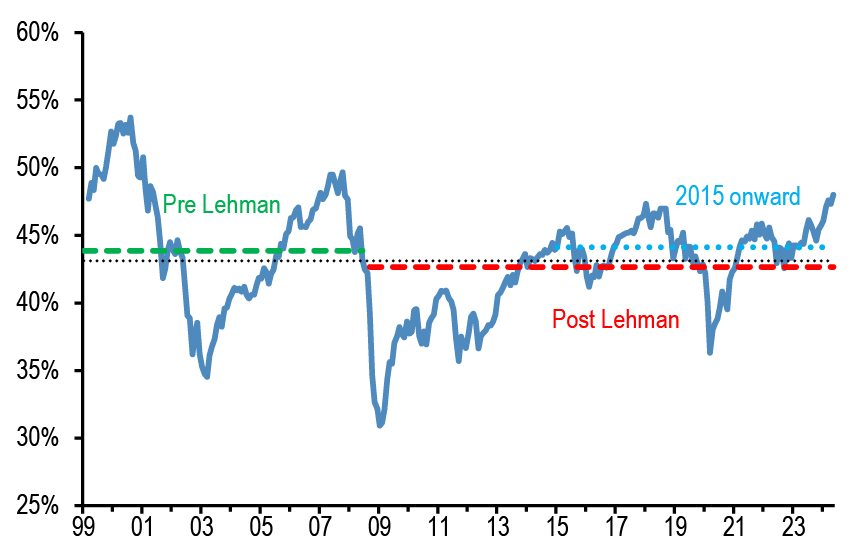

Chart A51: Implied equity allocation by non-bank investors globally

Global equities as % total holdings of equities/bonds/M2 by non-bank investors. Dotted lines are averages.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan

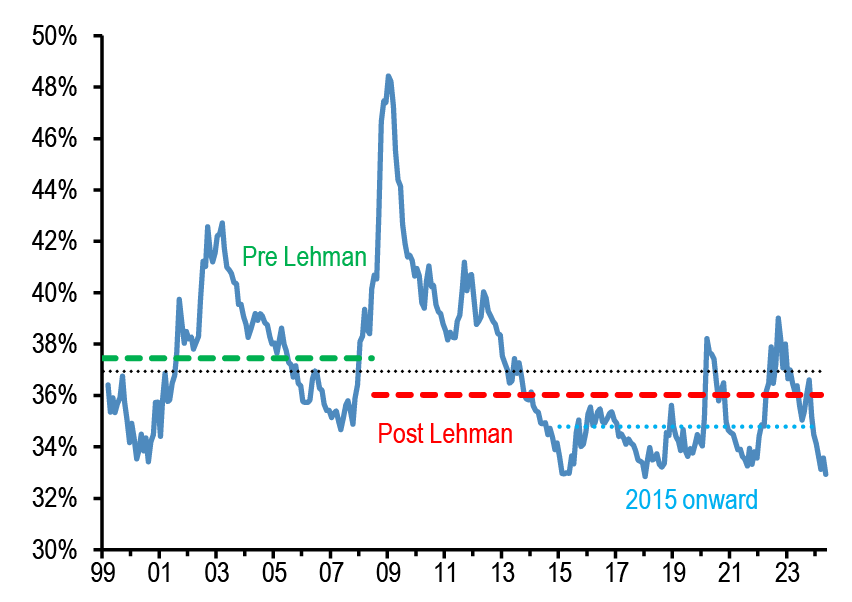

Chart A52: Implied bond allocation by non-bank investors globally

Global bonds as % total holdings of equities/bonds/M2 by non-bank investors. Dotted lines are averages.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan

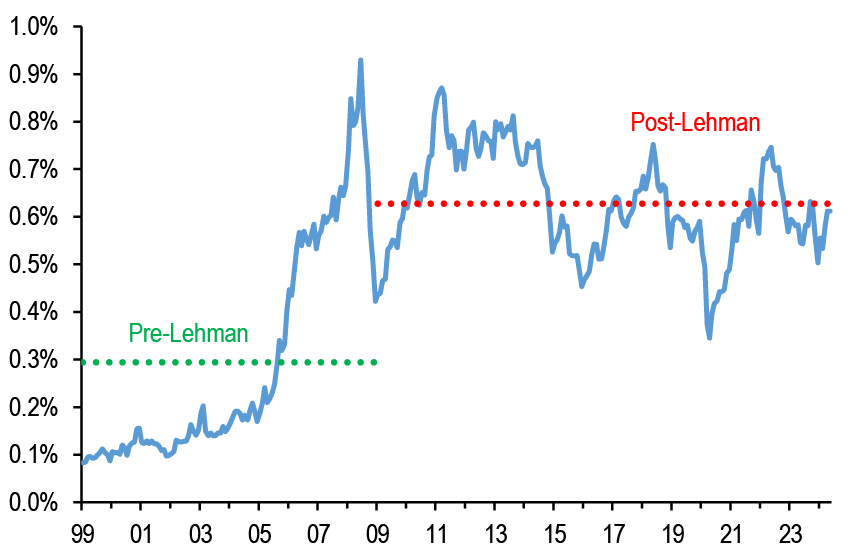

Chart A53: Implied cash allocation by non-bank investors globally

Global cash held by non-bank investors as % total holdings of equities/bonds/M2 by non-bank investors. Dotted lines are averages.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan

Chart A54: Implied commodity allocation by non-bank investors globally

Proxied by the open interest of commodity futures ex gold as % of the stock of equities, bonds and cash held by non-bank investors globally.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., J.P. Morgan